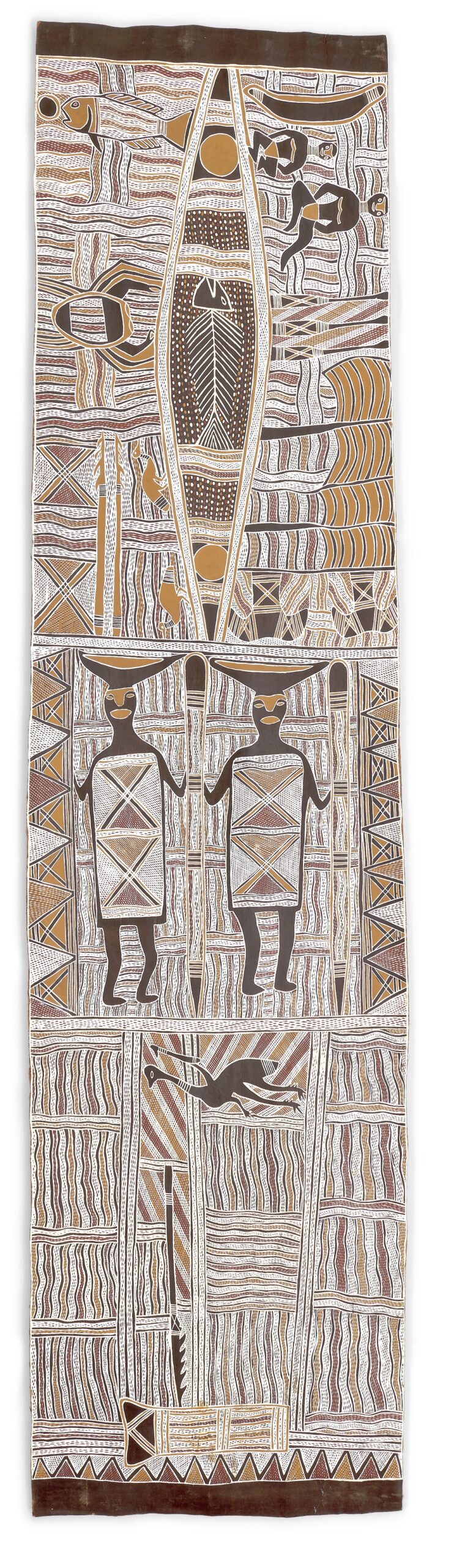

"My name is Ḻiyawaḏay Wirrpanda. I am going to tell you the story for the painting Maŋgalili Dhäwu | Maŋgalili Stories. This is my mother’s painting, but I am a djuŋgayi (caretaker) for these paintings. They belong to the Maŋgalili clan, but I am the caretaker. They show the sacred burial ground we call yiŋapuŋapu, the Emu ancestor named Wurrpaṉ and the spirts of the ancestral women, called Nyapililŋu.

First, I will tell you the story of yiŋapuŋapu,, a burial ground made in the sand. When we eat fish or anything else, we throw the bones into this ground. At the top of my mother’s painting, you can see the two old men sitting with their bark canoe and paddles and the yambirrku’ (Choerodon cyanodus, blue tusk fish). Even today, when we eat yambirrku’, we make sure to throw the bones into the yiŋapuŋapu,, and the sand crabs eat the rotten bones. They eat all the rotten bones. That is what my mother has

painted—here, you can see the bones, and these white marks are all the muṯimuṯi (sand crabs). The sand crabs eat it all. When we eat the fish and then chuck all the bones

into the center of the burial ground, the crabs come out of the ground and start eating. The crabs are also called gunyaṉ. The sand crabs will eat the rotten fish and climb on

top of one another, and they will not finish until they have eaten all the leftover flesh, leaving only the bones. The crabs will climb on top of one another when we throw the bones and flesh of the fish to the middle of the yiŋapuŋapu.

And when the crabs eat the fish, it gives us luck so that

when we go fishing again, we will get a lot of fish, because

we have thrown the bones and flesh right into the center

of the yiŋapuŋapu.

And this—here on the bark, where you can see all the

white dots—those are the tracks of the sand crabs. That is

how they make the tracks when they crawl. You see all the

dots? That is how the sand crab makes the tracks and the

way that it eats. We show this through our miny’tji (clan

designs). And that is what yiŋapuŋapu means. It is used

by specific clan groups, and we must hold on to it strongly

to keep this culture alive. The sands will open for Yolŋu

from the Maŋgalili, Dhaḻwaŋu and Maḏarrpa clan groups,

for they each have their own yiŋapuŋapu. Yes, each of

these clans has its own individual yiŋapuŋapu, but they tell

their own stories.

Here you can see the cloud that hangs over the sacred burial ground, and on the other side are two emus. Below them are our ancestors, Nyapililŋu. Those two are the Nyapililŋu spirits at Gurumburrawuy. They hold sacred possum-fur string and a wapitja (digging stick), and a cloud is hanging above them—that is the cloud there, on both sides. That story is different from the one of the yiŋapuŋapu.

And this one here is the story of Wurrpaṉ (the Emu ancestor). He was carrying a spear, and then he speared a rock. A rock called Yininydjurr is what he speared. And that rock stands in the saltwater, not on the shallow waters— this rock, here. Wurrpaṉ made that spear.

These stories are from a place in Djarrakpi called Gurumburrawuy; these stories are for everyone. This is my mother’s painting, and I have taken ownership of this

painting. I have taken this painting, and now I am telling the story to you. And that is it—that is the story, just a little bit of that story"

– ḺIYAWAḎAY WIRRPANDA

More Info

Galuma painted after her father, Narritjin Maymuru. Three panels on this bark are related events that occurred during Waŋarr (ancestral times). The dominant miny’tji (clan design) of wavy, alternately colored bands of cross hatching throughout the panels generally represent the sand dunes of Djarrakpi. The top panel refers to mortuary rites. Its central icon represents the Yiŋapuŋapu (sand sculpture) that keeps the contamination of death at bay.

The central panel depicts Nyapaliŋu (ancestral creator woman) with her digging stick and fruit basket. She is the Maŋgalili symbol of fertility knowledge and power. The bottom panel tells of the event that laid the foundation for the Maŋgalili clan. According to the artist, the subject of this work had not been painted before. A large and sacred rock lies at Djarrakpi. As seen in the painting, the rock was hit by the spear of the totemic emu. After it was speared, the rock manifested as raŋga (sacred ceremonial object).

– Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre

Additional Information

Decade

1996

Medium

Natural pigments on eucalyptus bark

Dimensions (IN)

116 1/8 x 34 1/2

Dimensions (CM)

295 x 88

Credit

Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia. Gift of John W. Kluge, 1997. 1996.0035.016.

Narrative

Maŋgalili

The Maŋgalili clan belongs to the Yirritja moiety. Their major spiritual theme revolves around the...

Songline

Yiŋapuŋapu

The yiŋapuŋapu is a low relief sand sculpture, elliptical in shape, that is used in...

Location

1990s

Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre began the 1990s in a phase of rebuilding. By the end of...

About The Artist(s)

Clan

Maŋgalili

Artist Dates

1951-2018

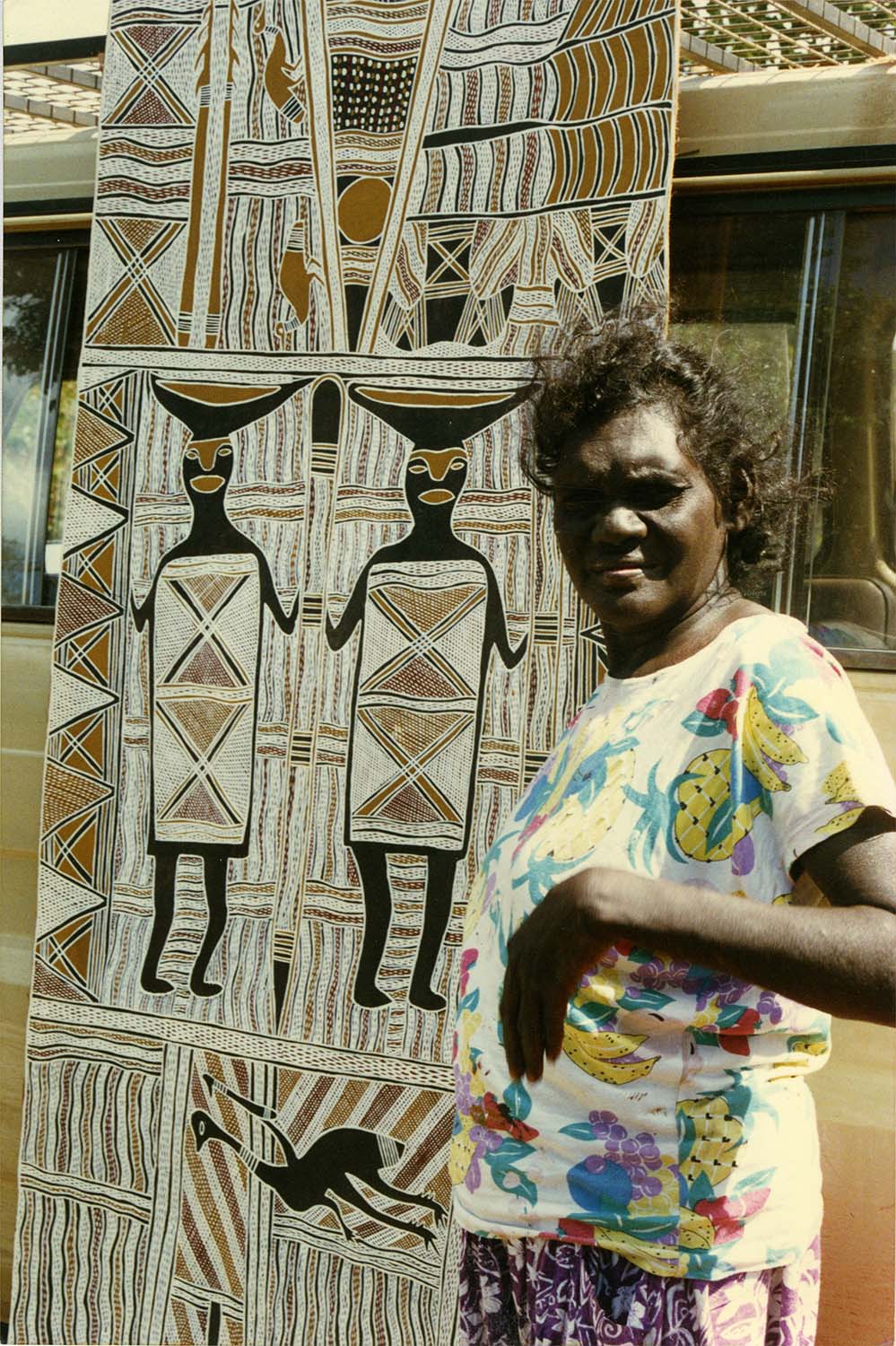

Galuma Maymuru

Galuma Maymuru was one of the first women to paint the maḏayin miny’tji (sacred clan designs). She was taught by her father Narritjin Maymuru. Galuma worked as a teacher at Bäniyala School and was influential in the Buwayak movement, in which the figurative elements of paintings were buried beneath more abstract designs. In 2003, she received the bark painting prize at the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards.

Collections Represented

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Berndt Museum of Anthropology at the University of Western Australia

Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia

Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory

National Museum of Australia

Sydney Opera House