In September 2022, Ishmael Marika traveled to the United States as part of a delegation of Yolŋu artists to attend the opening celebration for the exhibition Madayin: Eight Decades of Aboriginal Australian Bark Painting from Yirrkala at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College. Marika played a central role in the exhibition, as both a member of the curatorial team and by creating two major new video installations with Yirrkala’s multimedia unit The Mulka Project. The following conversation between Marika, Henry Skerritt and Kade McDonald was recorded via zoom following the delegation’s return to Yirrkala.

Henry Skerritt (HS): Maḏayin was seven years in the making: after such a long process of development, what was it like seeing to finally see exhibition?

Ishmael Marika (IM): I think the exhibition is great. I was really happy to see all the paintings together. It made me proud to see my grandmother [Ms. M. Wirrpanda’s] paintings and my father [Wanyubi Marika’s] painting and all the others. Seeing all those works, by the old people –they went before me– and seeing my video pieces there alongside them, it was like talking to the ancestors or talking to the spirits.

And I enjoyed talking to people in America and telling them about the Yolŋu people—that we still speak our own languages; that we have our own songlines; and that we do paintings to represent sea Country and inland Country and all that stuff. It was an opportunity to tell them that the painted designs do not exist by themselves – they are a map of the Country and the boundaries – telling you whose songlines and language groups each painting belongs to. The old people documented that in those barks – in the early days – and that practice continues through to today. People don’t know these stories! We don’t document them in a book, we document them on bark. We have been given these stories through the songlines, and we share them through the songlines and through bark painting. We show how the songlines move through the Country, and how we see the reality of the songlines, as they travel from each area, connecting all the places.

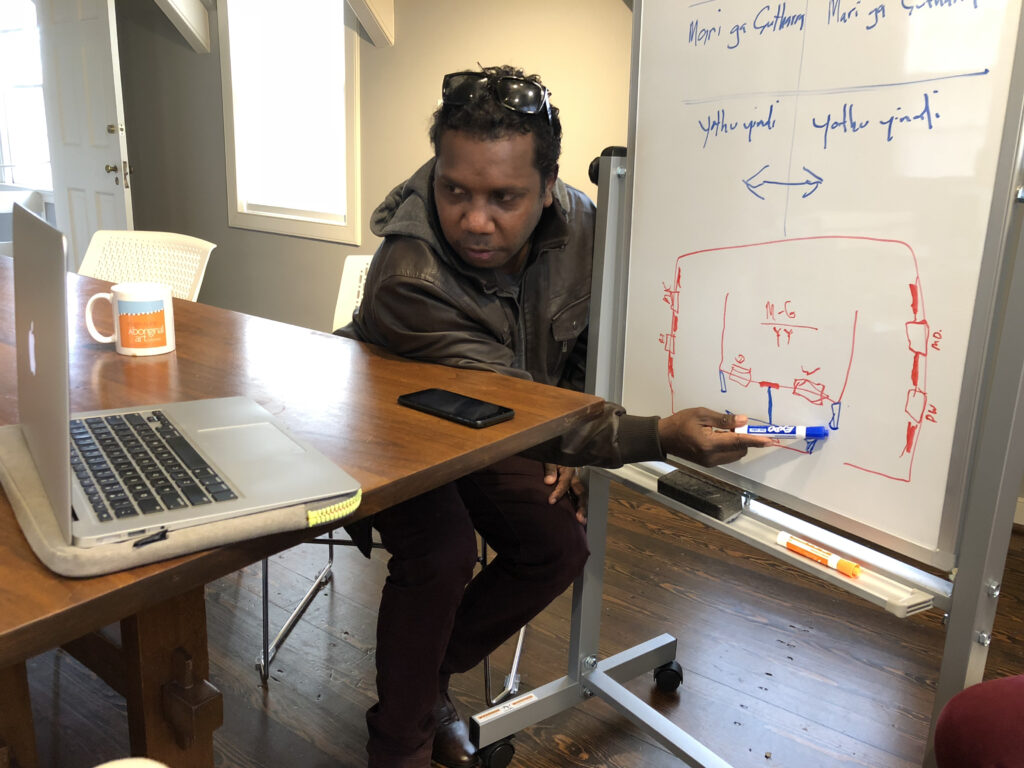

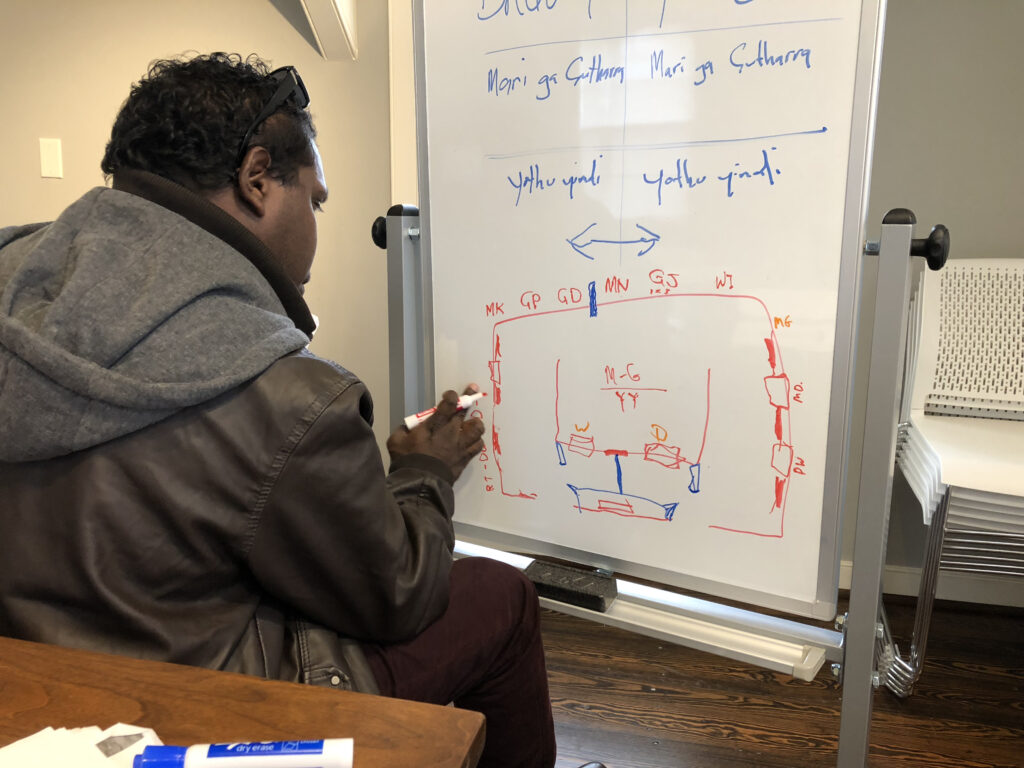

Photo by Rob Strong.

Kade McDonald (KM): Your videos are a really powerful component of the exhibition. Can you tell us a little about the ideas behind them? Barrkuŋu Ganydjarr | Strength from Afar (2022) is a four-channel video that is staggered throughout the exhibition. It features a single dancer [Gatjarrarra Marika] who moves between the four screens performing different ceremonial dances. What was the inspiration for this piece?

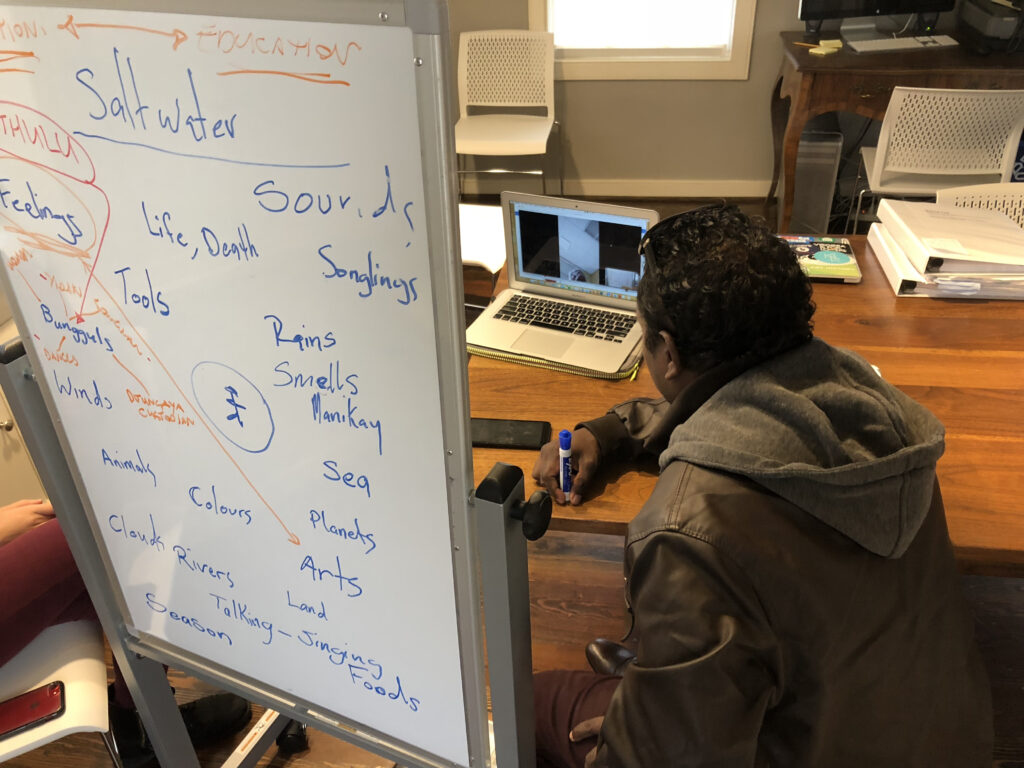

IM: In 2018, I went to the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection at the University of Virginia with and Mr. Waṉambi. We went to look at the paintings from the early days, from the 1950s and 60s, that were done by the old people. Mr. Waṉambi really wanted to have video in the exhibition, to bring the art to life. There are a lot of paintings in the exhibition, but people don’t know the meaning or background to these artworks. They might see it and think it is good art, but then they must go to the catalogue to find the full story. So, Mr. Waṉambi said, “OK, we need to work with video to explain about our clans, to show, this is the Dhaḻwaŋu clan’s paintings; this is their buŋgul (dance); this is their manikay (ceremonial song); and they all go together. We wanted to show that these things are all linked; that the art, the dance, and the songlines are all connected.

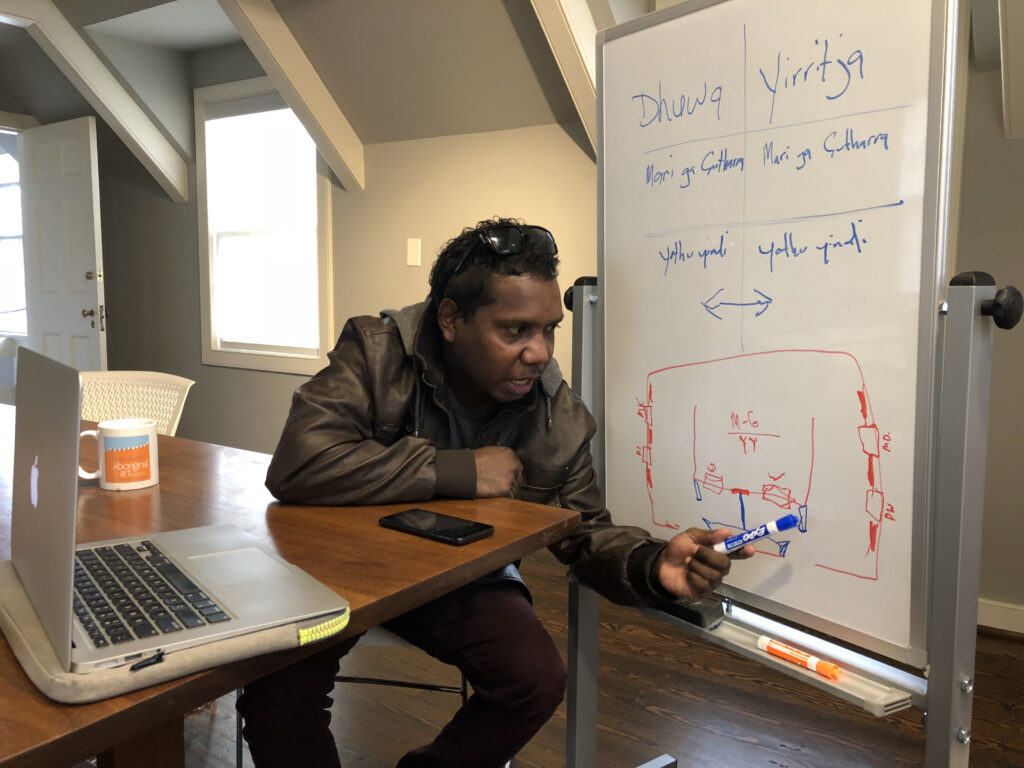

On our way to Virginia, we stopped in Los Angeles. Mr. Waṉambi and I saw a video installation [by the Icelandic artist Ragner Kjartansson]. It had multiple screens with different people playing drums and guitars and other instruments. Mr. Waṉambi said, “I want a video like that, but done our way.” He said, “I’m going to make a video for the Maḏayin exhibition and it’s going to have the buŋgul and manikay for the clans representing the paintings. So, each of the four screens represents a different clan, and it goes around in a cycle. And the dancers will wear the colors representing their clan members. So, for instance, in the Dhaḻwaŋu video, the dancer is wearing red.

Here in northeast Arnhem land everyone is either Yirritja or Dhuwa. Every place is either Yirritja or Dhuwa, as are the plants, the animals and the waters. In the video, there is a Yirritja half, represented by the Maḏarrpa and Dhaḻwaŋu clans, and a Dhuwa half, represented by the Ḏäṯiwuy and Djapu’ clans. The cycle goes from Ḏäṯiwuy to Dhaḻwaŋu to Djapu’ to Maḏarrpa, jumping between each clan, going round in a circle, to represent Yirritja and Dhuwa.

During that trip in 2018, Mr. Waṉambi got sick, and ended up in hospital, but we kept working and planning for the exhibition. I was glad I could be there to help him out. He was sick, which is why I stepped in.

HS: Could you tell us the significance of the title, Barrkuŋu Ganydjarr?

IM: Barrkuŋu Ganydjarr is the strength that comes from far away–the strength that travels. One of the songlines in the video is sung by Djambawa Marawili. He sings of Yarrwarri, the Queen Fish (Scomberoides commersonianus), which travels from far down south, from near Numbulwar, all the way to Blue Mud Bay. It takes great strength to travel this distance. And that is like the art that came from here in northeast Arnhem Land and traveled all the way to the other side of the world. The art has strength, and it traveled this great distance to show everybody in the world who we are. That is why I called the video Strength from Afar.

HS: You mentioned Mr. Waṉambi, who played such an important role in curating and developing the exhibition. It really felt like he was present at the opening celebrations at Dartmouth.

IM: Yes, Mr. Waṉambi, he was there with us in spirit. That was why I acknowledged him in the manikay at the opening dinner. I felt he was present: he was there with us, so I had to say thank you through the songlines. The song I sang is about a spirit man named Wawit from the Marrakulu clan [the same clan as Mr. Waṉambi]. The spirit man was hunting for oysters, going down to the beach and eating oysters on the rocks, while the Djapu’ water is crashing on the rocks. There is gathul—mangrove trees—and also the water, crashing into that sand. So, the song represents the Marrakulu clan and the spirit of the ancestors that traveled to collect oysters down the beach. Through that songline, I thanked Mr. Waṉambi for all the hard work that he put into organizing the exhibition.

Likewise, the song that Djambawa Marawili sang [at the opening ceremony] related to the deep waters of Muŋurru. Muŋurru, the saltwater of Blue Mud Bay mixes with the Marrakulu water named Guṯultja. So, we painted our faces with gapaṉ (white pipe clay), representing the Marrakulu clan, representing Mr. Waṉambi. Djambawa was singing Muŋurru, but we did not have Mr. Waṉambi to sing for Guṯultja, so that is why we put the white ochre on our face, to represent him. We were reaching out to that spirit to join with the other spirit of the water.

KM: That was a very powerful moment at the opening when you were welcomed with song by the Wabanaki leader Chris Newell with the exchange of songs and gifts.

IM: Yes, that was very good, seeing the Native people welcoming us and exchanging gifts. Because they are the landowners, we want to connect with them first—their spirits and souls and mind, because everyone is different and has different culture and Law and ancestors. We wanted to acknowledge the traditional landowners and their ancestors and Law, ceremony and designs. We wanted to connect through our art and our songlines. They were good people, looking after us, and the students, were good students. They will learn about Yolŋu people through the art and songlines in the exhibition. It will talk to their spirit. It’s all about connections– gurruṯu (the Yolŋu kinship system)– everybody is connected through the miny’tji (painted designs) – all the miny’tji – it doesn’t matter if it is Dhuwa or Yirritja, we are all connected through the gurruṯu system.

HS: When visitors enter the exhibition at the Hood Museum, they are greeted by another video installation titled Gapu Muŋurru ga Baḻamumu Mirikindi | Deep Waters of the Dhuwa and Yirritja Moieties, 2022. Could you tell us about this work?

IM: Yes, the big video at the entrance is about Dhuwa and Yirritja welcoming everyone to the exhibition. Beneath the waters are two songmen—Djambawa Marawili and Mawalan #2 Marika. They are singing a welcoming manikay – or rather, a strengthening manikay, a big name manikay. When you enter into men’s ceremony, if you go to the Yirritja side you will hear Yirritja people singing Gapu Muŋurru with the bilma (clapsticks). They use big, long clapsticks and will sing all night, sometimes through till the break of dawn. Listening to those songmen gives you strength; it gives you peace, harmony, kindness and happiness. And sometimes you will feel sorrow and think about special people in your life. So, the song can make you emotional, but it will also bring you strength, just as it strengthens the artworks—Dhuwa and Yirritja—so that everyone can enjoy seeing all the paintings. That is what that video means—it welcomes you and gives you strength before you enter the exhibition.

As I said before, everything is Yirritja and Dhuwa – we are separated by these two moieties, but everyone is connected through the gurruṯu system. Dhuwa can only marry Yirritja; and Yirritja can only marry Dhuwa. We marry the opposite. This also tells us our boundaries. I’m Dhuwa, but my mother is Yirritja, so I must pay respect to my mother and act as a custodian or caretaker for my mother’s clan, to speak on their behalf. But I am Dhuwa, so I can also jump in and talk about my father’s side, and take a role for them, for if my father is gone, I am the next leader of my father’s people. The same goes for my märi-pulu, my mother’s mother’s people – I must speak for their ceremony as well. The same goes for my sister clan or yapa-pulu, which is the Marrakulu clan. I have a role to direct or pay respect to them. Through these connections we have a journey that goes through the generations.

And we must communicate to each other—for instance, I must make other clan members aware that I am coming to their land or that I will be talking about a particular area. I will pass my message to those people, saying “OK, this is your boundary, but I will talk about my mother’s paintings or my mother’s mother’s painting.” It is all connected. And as the songlines travel, they remain connected, but the language changes. For example, for my clan, Rirratjiŋu, the songline travels west and changes from Dhuwal to Djambarrpuyŋu, but the story is the same. It keeps traveling from east to west, but the language is changing. Our systems and our languages are many. Americans don’t know who are Yirritja and who are Dhuwa, or that there are six or seven different dialects. People think we all speak one language – Yolŋu Matha – but Yolŋu Matha has many different languages – Dhuwala, Dhuwal, Dhay’yi, Dhaŋu and so on.

KM: What was the highlight of the trip for you?

IM: The highlight for me was talking to students and lecturing at the university, talking about different artworks to the students. And not just bark paintings: we talked about digital art pieces, working with video and audio and how Gunybi Ganambarr works with metals; and Djuwakan Marika talked about playing yiḏaki (didjeridu) and how that links with the songlines. Yiḏaki is like the click-track to the songlines, giving you the rhythm and strength. You have to follow the yiḏaki, and the songman and the yiḏaki man must communicate, when to take a breath and when to keep going. It was important, talking with the students and the public, not just about the artworks, but about the bilma, the yiḏaki, the manikay and even the sound of the water, the wind blowing through the land or the call of the birds.

The first song I sang [at the media preview for the exhibition] was the song of the brolga. It is a very significant bird. You hear the sound of the brolga in the distance, but you don’t see it. You can hear it, and it feels close to you, but it is in the far distance, circling, looking for food. It is seen on the sun, giving the birds life and bringing new life to the bird. That is what the brolga manikay means–it is about bringing new life into the earth and the land, by the sound of the brolga circling in the distance.

American audiences came to me saying “thank you,” because I was talking and explaining to them about the paintings and the video pieces I’d worked on. It was great to be able to explain about some of the paintings, such as my grandmother’s paintings [Retja I (2017) and Retja II 2018)]which are all about bush food. She grew up eating all that food, but it is not documented, and young people are not learning about it. They are growing up eating shop food and not going out and getting healthy bush foods. That is why she painted it, to document the stories of the food and plants and what they look like, where you find them, in the water or dry areas. She was close to me my grandmother, and I always asked questions about what she was working on. She would tell me stories during my lunch break, and so I kept those stories that she told me, and I shared them with the people who came to see her artworks. I told them the stories she told me.

KM: That strikes me as one of the most important things about the Maḏayin exhibition. At the opening, Djambawa made the point that the older paintings are just as relevant as the new ones, because they tell the same stories and speak to the same gurruṯu connections, and that culture, language, the songlines remain unbroken.

IM: Yes, they are still the same, the same stories. The men tell the stories through the songlines and the same goes for the women, through the milkarri or crying songs. They tell the same stories. If the men sing of the travel of fire from Maḏarrpa to Gumatj Country, the women will cry it through the milkarri, following the spirit as it moves across the land.