The following interview was recorded with Henry Skerritt and Kade McDonald in Darwin, April 26, 2023. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Nhamirri bukmak. How are you everybody? First, I am going to introduce myself. I am an artist, and I will tell you where I come from and about my family: my mother, father and sister are all artists. Yo! But first I will tell you about myself and about when I was young and started to do my art, on small barks. And then my father saw it and gave me another bark. That was how I learned, and how my father taught me about painting. That is what I am going to talk about. Yo! But first, I am going to introduce myself. Ma.

My name is Marrnyula Munuŋgurr and my homeland is Wäṉḏawuy. I was living at Wäṉḏawuy when I first became an artist. Wäṉḏawuy is in an outstation, it is inland, freshwater and it belongs to the Djapu’. Mäṉa (the Shark) is our totem. It traveled from Djambarrpuyŋu Country, all the way to Djapu’ Country at Wäṉḏawuy. Sometimes I tell the story of Mäṉa, but sometimes there is too much in my head.

Yes, I learned at Wäṉḏawuy from my father [Djutjatjutja Munuŋgurr]. He showed me how to cut the bark, how to straighten it out, and then how to use sandpaper to smooth it up for painting. I was watching my father, wondering what to do next. He gave me a paint brush to paint on a small bark. “What can I do Dad?” I was asking my father. And he said, “Any picture you want, you can draw on the bark.” So, I said, “I’ll do a painting about hunting, about how Yolŋu go catch fish, or hunt turtle; about how we get the spear for fishing, and cook the fish on the fire, sitting under the tree, like a picnic nhäwi.”

And then I asked, “What’s the next drawing, nhäwi?” My father got a pen and paper and said, “You can draw our designs, Djapu’ designs,” and he drew them on a piece of paper for me. Then he handed me marwaṯ and gapaṉ to do the outline, yes, hairbrush and white clay. I took the brush and started doing my painting on bark. Then, my father gave me a big bark. He said, “Try and paint on this big one.” And so, we worked together. My father sat close to me and told me what to do, and showed me how to draw the shark and the liver on the shark. All the time, he was telling me stories about the paintings and designs.

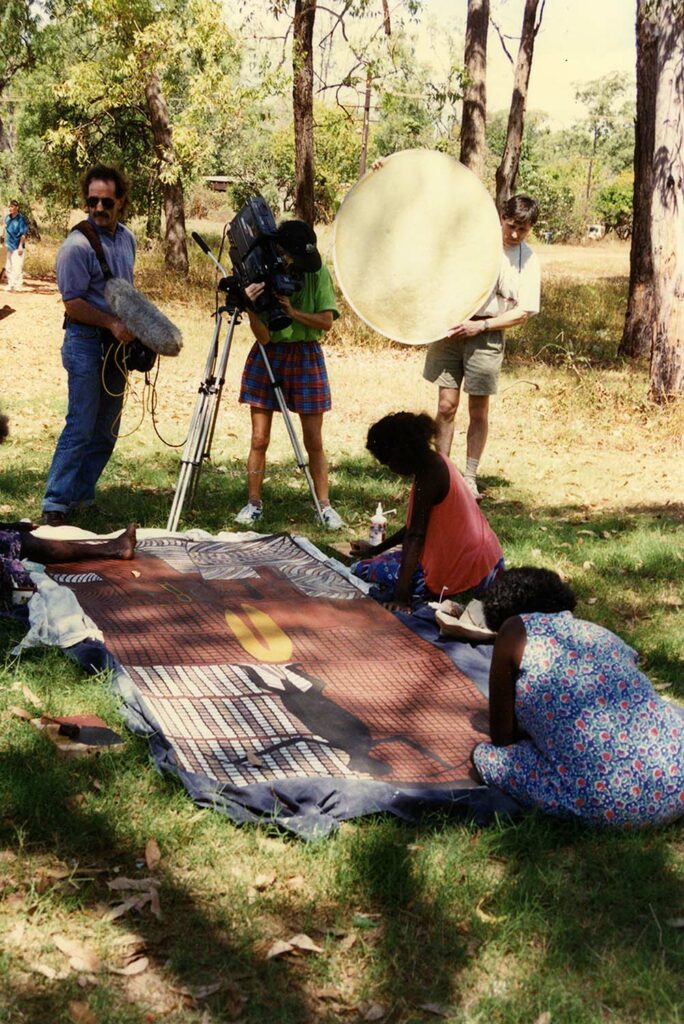

So, I kept painting. At the same time, I taught the children at school, telling them about our designs, Djapu’ designs. And when I finished a painting, I would take it to Buku-Larrŋgay Art Centre to sell it. Buku-Larrŋgay is our art centre. We bring our art to Buku so they can send it to all the galleries. I worked at Buku-Larrŋgay with Steve Fox for a long time, and then with Andrew Blake. While I was working at the art centre, Andrew Blake went out and cut all these big barks and brought them back for all the artists. All the artists came to Buku-Larrŋgay to paint, sitting inside the museum working on big barks. And me, and my sister Rerrkiwaŋa, and my mother Noŋgirrŋa, we all worked together, helping my father with his paintings.

That was when we painted that bathala ṉuwayak [big bark]. On the top is my Dad’s painting, Bol’ŋu, the Thunderman. Bol’ŋu is the Thunderman, yo. In the middle is the shark liver, the Yothu Djukurr. Like, we adopted you, so you are the Yothu Djukurr, the liver of the shark. Yothu Yindi [mother and child]. Yindi is the shark, Yothu is the liver of the shark, djukurr. That is djukurr in the middle. That is all Djapu’ miny’tji – one straight line, from the old paintings to the new ones. It is the same miny’tji you can see in that painting by the old man, my grandfather [Woŋgu Munuŋgurr]. You can see, the story is still the same. One straight line from that old man to his sons and grandchildren. Like rain coming down.

Bol’ŋu brings the rain. His spear is the cloud. When you see him holding his spear, it is the clouds. And you can see people dancing that cloud, holding the spear above their head. It is the cloud dance for Bol’ŋu who brings the rain. Yes, Bol’ŋu brings the rain, filling the river with gapu (water), freshwater. The miny’tji comes from the rain and the water. It is important to know where the paintings belong, where they come from. Paintings tell a story and they belong to that place. The miny’tj comes from that place, Wäṉḏawuy. We are Djapu’ people working on Djapu’ miny’tji. So, when people come to Wäṉḏawuy, they cannot steal our designs, because it is for our land. That miny’tji belongs to that place. Ŋanapurru. It is ours!It is our design, ŋanapurru miny’tji. Those designs belong to us, the Djapu’ clan.

Wäṉḏawuy is my homeland, but I was living at Yirrkala for a long while, working on my art. And then I started working in the Print Space, maybe in 1996. I worked there with Basil Hall, he came to help me set up the print machine and studio. I was working with Basil Hall and we had a workshop with all the old ladies. They’re gone now, all those old lady artists. Then I went to train as a printmaker, and Diane Blake helped me. We were both working together at the Print Space, working with the old ladies. Young people started coming in, they wanted to work on prints too. The old ladies loved doing printing and so did the young people. It was a good way for young people to learn about their designs. It’s still the same, you see, like painting on bark. It’s the same story, outside nhäwi, but it’s a good way to show it to kids, how to do our art, so that later they can learn to be painters.

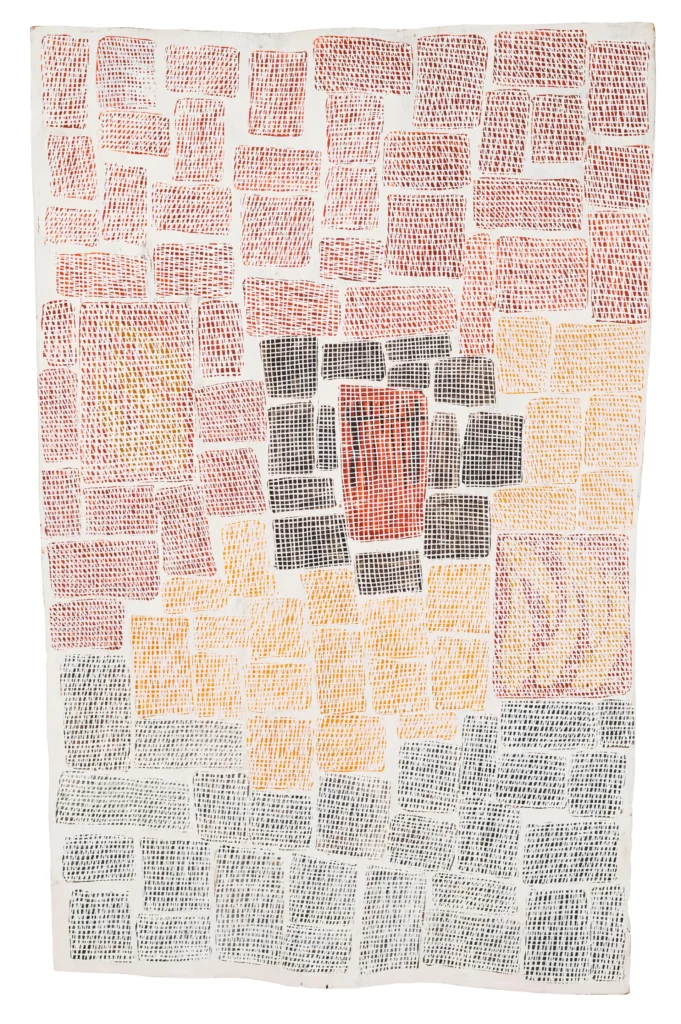

I had been working at the art centre for a long time, helping my father and mother with their bark paintings, and also doing my own. And I began to see lots of leftover bark pieces, just lying on the ground. They were all the leftover bits, you know, when you cut the bark where it is cracked. I looked at those pieces and wondered, “How can I do my art? I don’t want to leave those pieces on the side.” So I started picking up those little pieces and working on them. I was cutting those leftover strips, making small barks and working on them while I was doing printing at Buku-Larrŋgay.

And then, one day, I asked Kade McDonald if it was alright to paint my hairbrush outline on these small ones and put them all together, like a puzzle. That was my idea. And he said, “Ma! It’s your idea, sister, you can do whatever you like.” So, the first one I did was for an exhibition in Melbourne. As I was putting it up on the wall, I was thinking, “What can I do?” And then I realized, I could do Ganybu (the fishtrap). That was my first exhibition of small barks. Then, when I came back from Melbourne, I kept thinking, “What can I do next?” I thought about the shark, and about yothu djukurr. And so, I made that out of small barks. That one went to Outstation Gallery in Darwin. The third one I did was Wukiḏi. And then you asked me to work on a really big one for America, that’s gapu, the freshwater miny’tji.

I’m still working on small barks, but now I am also painting the small ones on big barks, like the Telstra one. Because that’s my idea and it’s my designs, and I am doing my own designs on those barks. It’s a different way, but you can see what I am doing: the same miny’tji, Djapu’ miny’tji. It’s a different way of showing it, but it is still the same story. Freshwater miny’tji. I need to do it differently because there are lots of women working now, all my sisters. You see, they all want to be artists. Many mob in my family are doing Djapu’ miny’tji. Like Yimula [Munuŋgurr], she’s doing Djapu’ miny’tji. You can see her paintings at Buku-Larrŋgay. But I am painting in a different way now. The same miny’tji, but just in different ways. It’s just my style. Because they’re doing it their way, I’m doing a different style. I still want to do that other style, but I don’t know, I’m always thinking. And it’s hard to work now because I am staying in Darwin. But as I said, if you put all those Djapu’ paintings side by side, you will see it is the same story. The story doesn’t change, from the old man, my grandfather, to my father and then myself.

My father and mother, we all worked together, giving each other our knowledge. Gurruṯu is how we are all connected. So, for instance, my ŋäṉḏi (mother) is Yirritja, and she knows her Maḏarrpa miny’tji. My mother’s country is at Yilpara. That is my ŋäṉḏipulu. Maḏarrpa is our one mother clan. So Noŋgirrŋa is doing her miny’tji, my ŋäṉḏipulu. But for a long time, she was helping my dad with his Dhuwa miny’tji. After he died, she got her bark, and we asked her to do her own Yirritja designs. She doing these designs now, her own designs for Baratjula. That’s her design, her hand and her knowledge, and those designs are hers to do what she likes with.

Me and Rerrki, we are doing our own Dhuwa miny’tji. But sometimes, Rerrki does Yirritja miny’tj. She does both Djapu’ and Gumatj miny’tji, Dhuwa ga Yirritja. Sometimes Dhuwa, sometimes Yirritja, because she got permission from her husband Yälpi [Yunupiŋu] to paint his Yirritja designs. Yes, your malu asked her to do that Gumatj miny’tji. I can’t do Yirritja miny’tji, I just paint Djapu’ designs. But you can paint Yirritja designs if they ask you. Like, if they asked me to do Maḏarrpa miny’tji, because that is my mother’s clan, my ŋäṉḏipulu. I would ask a Maḏarrpa person, “Is it alright for me to do my mother’s painting?” And they would say, “Yes,” because I am a djungaya. For my father and my sister, Maḏarrpa is our mother clan. Gumatj is also our ŋäṉḏipulu. Madarrpa and Gumatj have the same manikay but different ḻikan. When you look at their miny’tji, they have different diamonds: the Gumatj have the small diamonds. But they are both ŋäṉḏipulu. Our märi’pulu [mother’s mother’s clan] is Gälpu and our wakupulu [child’s clan] is Dhaḻwaŋu. That is how Gurruṯu works, connecting us.

This is our culture, our Rom. It is the Law for Yolŋu people. Strong culture and strong Law for Yolŋu. We want to make art to show all the people, everywhere in the world, that we hold this knowledge. And so we can teach our children, that they can learn how to live in the right way. Yolŋu need to understand about their culture and Law. They need to know that it is important. Our miny’tji and our djakiri are our foundations, passed down from what our old people taught us. That is our knowledge, our culture, our art. And we can teach others, for the future. Yes. That’s our culture. Ma.