Origins

While visiting art storage at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C., Djambawa was further surprised to see works by his uncles and grandparents collected in 1948 during the American Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. “I have come here to America,” he declared, “and found my Maḏayin miny’tji [sacred designs]. And it is good.”

It’s really important to show those old paintings and to recognize that we Yolŋu have enduring patterns that connect us to our country. I’m really proud to make the connection to America. The art went first – all those old paintings in the gallery. What follows is reconciliation – and passing the knowledge to America through our art. Because art is really important to us. It represents our soul and our mind.

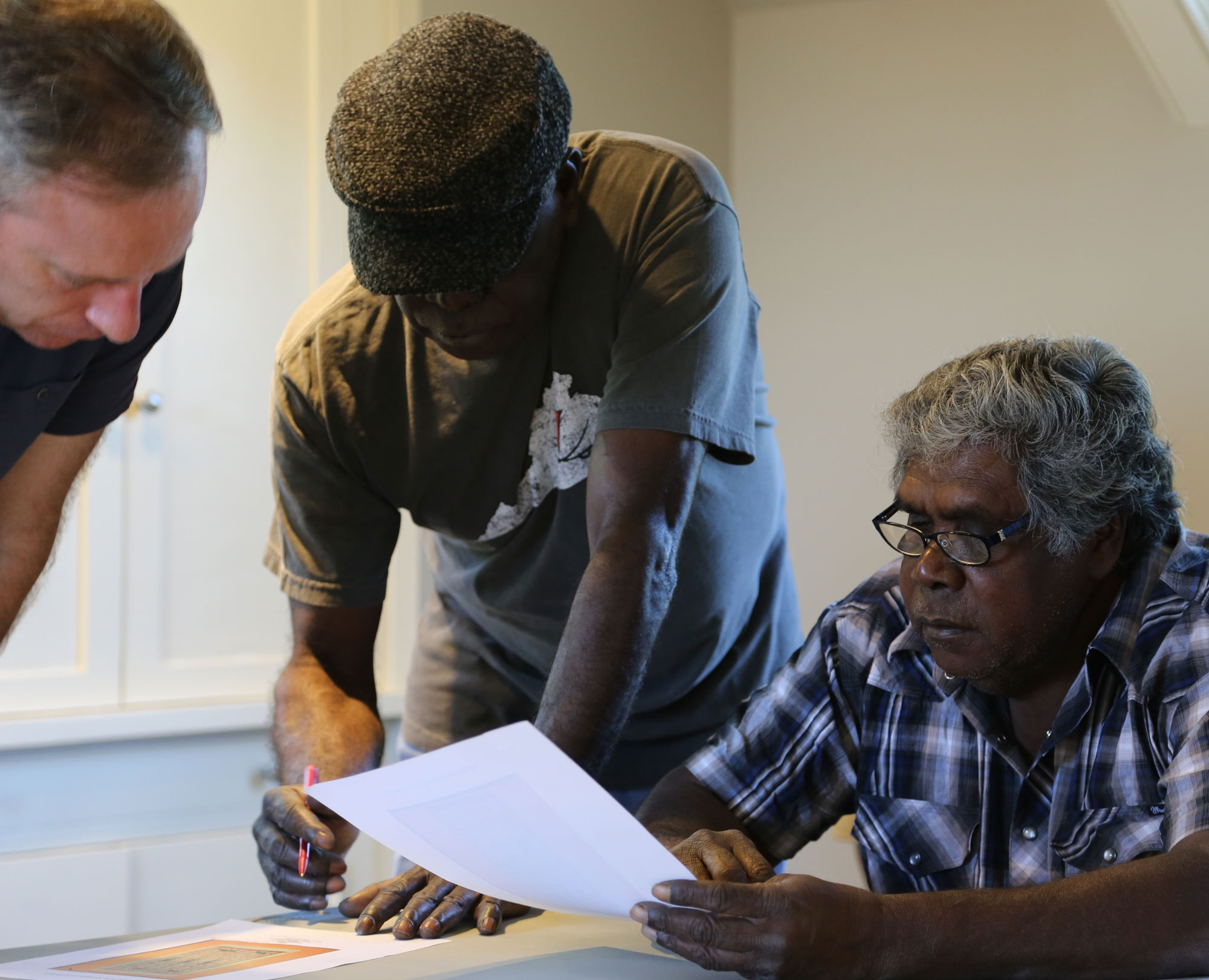

Finding such significant Yolŋu bark paintings in the United States, Djambawa saw both the need and opportunity to awaken these works as a means of strengthening Yolŋu culture by presenting its enduring authority to the world. Djambawa charged Kluge-Ruhe with curating a traveling exhibition that would, in his words, “Tell the whole story of Yolŋu bark painting from Dr. Thomson’s time to the present.” For Djambawa, this was an unfolding story of Yolŋu artists sharing their culture with the world.

To learn more about how the project has come together, explore the blog.

This exhibition is a great opportunity for our people to come and share our culture, and do research on our paintings. We have these paintings for future generations to look upon and gain respect for those people that came before. In that way, today we are making art for the children who are coming behind us, giving a clear message to them. It is something that we really need to make the art move into our eyes and our souls, to make it really do something important.

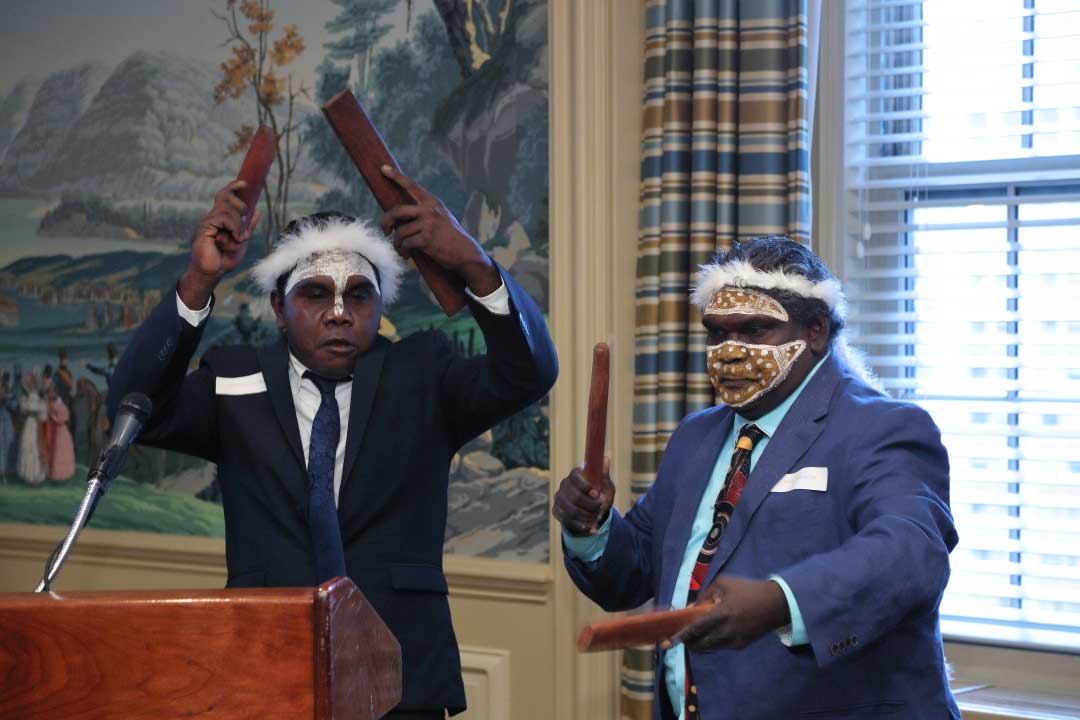

In May 2017, the project was officially launched by former Prime Minister of Australia, Kevin Rudd AC with Wukun Waṉambi and Yinimala Gumana. It was given the name Maḏayin: a Yolŋu term referring to both the sacred and the beautiful. A word with strong ceremonial associations, the tile reflected the seriousness of the project in the eyes of its curators. As Waṉambi notes:

We wanted to open another door for maḏayin, to translate its beauty, to say “this is a beautiful painting, this is a beautiful Country.” That is how we curators explained it to Yolŋu people and eventually they agreed to get involved, and agreed to put the name Maḏayin on our great project. And we will take it to Washington, DC and Los Angeles to show our identity. . . .For the bark tells of our identity, our kinship and our destiny.

What is Bark Painting