Kluge-Ruhe’s bark painting commissions for Madayin made their Australian debut in October 2019 during Tarnanthi, a city-wide festival of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander arts hosted by the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide. The exhibition Dhawut (Fly Away) presented 28 contemporary artworks by Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre’s most respected artists. Hung on black walls with dramatic lighting, these bark paintings stood out as the masterpieces they are. The exhibition title makes reference to the commissions leaving Australia for the USA at the conclusion of Tarnanthi.

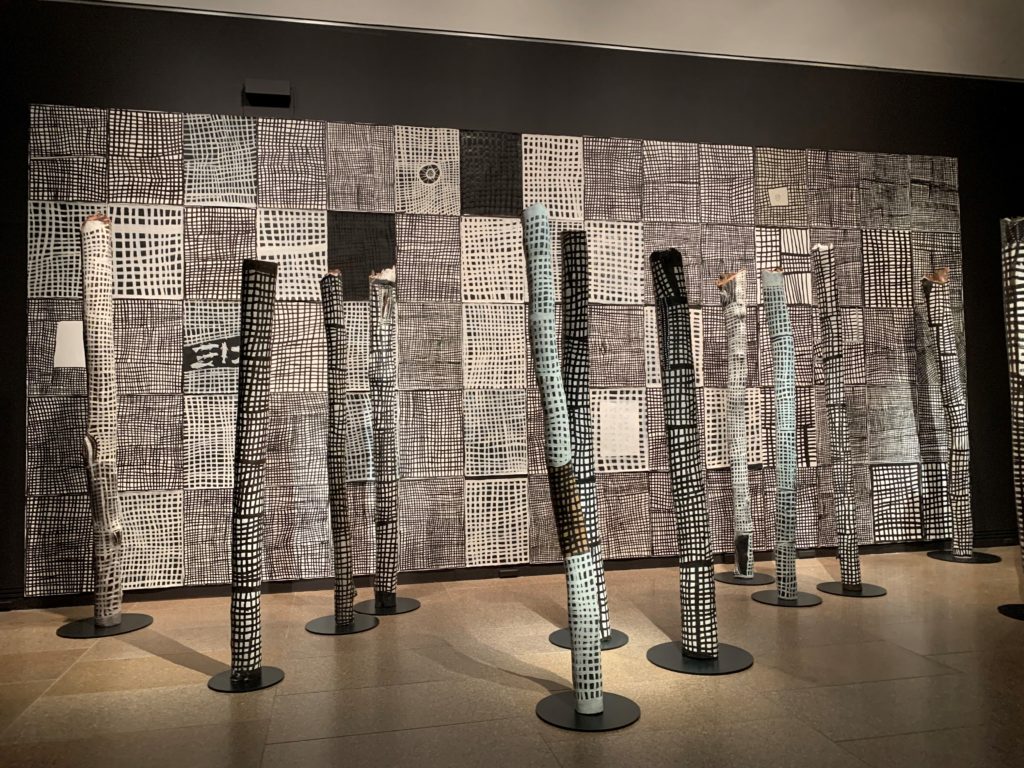

Artworks by Buku-Larrŋgay artists featured prominently at the AGSA and elsewhere during Tarnanthi. Descending the gallery’s sweeping staircase, visitors encountered a monumental piece of metal etched with miny’tji by Guynbi Ganambarr and Noŋgirrŋa Marawili’s electric pink bark paintings. Another gallery featured a massive wall covered with 75 paintings on paper by Noŋgirrŋa, variations of black and white lines offset by memorial poles painted with the same bold patterns. The gallery adjacent to Dhawut contained an installation of Wukun Waṉambi’s memorial poles and a mesmerizing light show of his signature schools of fish “swimming” through the gallery, across the walls and around the poles. Visitors were literally submerged in his artwork. Yolngu opened the festival with a powerful display of cultural authority asserted through song and dance.

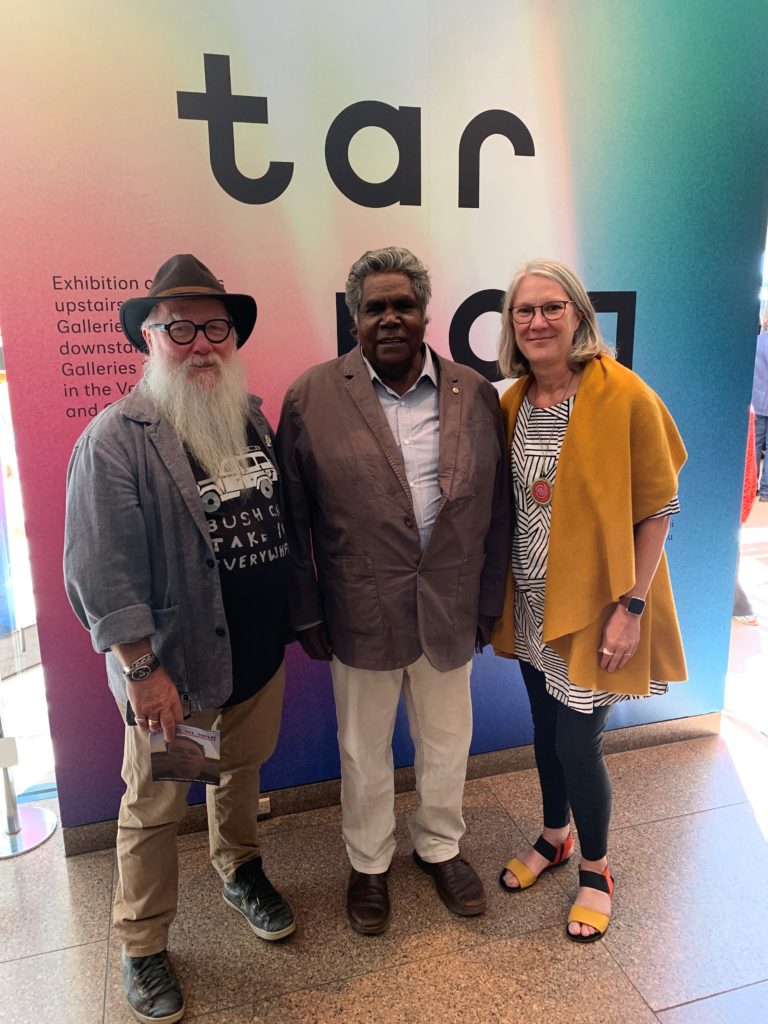

Tarnanthi attracted friends from across Australia and internationally. I was delighted to meet Steve Fox, former Art and Craft Advisor at Buku-Larrŋgay in the 1980s. He presented me with a very rare copy of Baniyala Artworks, a small catalog written by Djambawa Marawili and printed by the Yirrkala Community School Literature Production Centre. Like Madayin, the exhibition Baniyala Artworks was the brainchild of Djambawa, who believed Yolngu artists were creating some of the finest contemporary artworks of the day. It was one of the first major exhibitions from Buku-Larrŋgay to go to Sydney. It is no surprise, therefore, that Djambawa also conceived of Madayin, which will be the first major exhibition of Yolngu bark painting to tour the USA.

Tarnanthi demonstrated that Yolngu bark paintings are among the finest contemporary art being produced in Australia. It is an honor to share this magnificent art form with new audiences in the USA and worldwide through the Madayin exhibition, catalog and virtual resource.