Originally published in The Cavalier Daily, February 8, 2024.

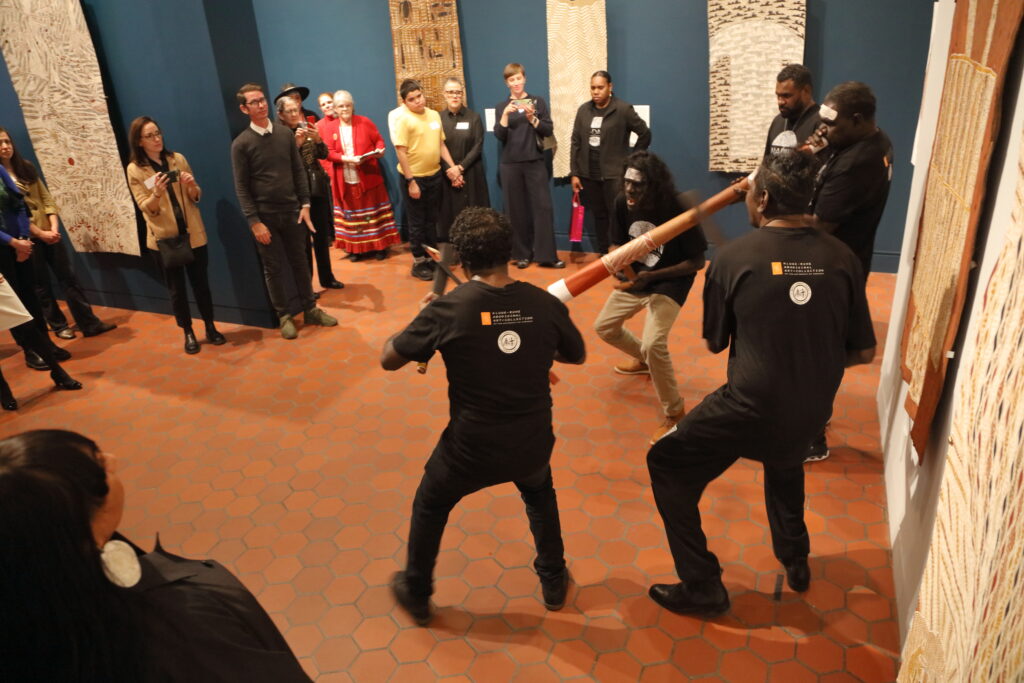

A pounding voice chants rhythmically alongside a projection of waves crashing as one enters the Fralin Museum of Art. The museum’s newest exhibit, titled “Madayin: Eight Decades of Aboriginal Australian Bark Painting from Yirrkala,” is an all-encompassing sensory experience that showcases traditional bark paintings of the Yolngu Aboriginal Australians.

For millennia, Yolngu people have been partaking in this ever-flowing, continuous art. The method of creation for bark paintings involves stripping Eucalyptus bark, which is flattened, dried and sanded to create an optimal surface for painting.

Then, Yolngu artists use natural pigments and ochres alongside water and an adhesive binder to create a material that can be used for paint. They use this paint to depict their respective family’s deeply important clan designs — called miny’tji — onto the bark.

When it comes to the name of the exhibit, “Madayin” roughly translates to mean the sacred, or something extremely sublime or beautiful. From the bark paintings to the connections being created by Yolngu artists, this exhibit fully encompasses the meaning of “Madayin”.

A big misconception in Western interpretations of Aboriginal and Indigenous art is that it cannot be modern. However, the paintings in “Madayin” are indeed contemporary art. While these pieces are deeply rooted in a rich artistic tradition, they are ever flowing and ever evolving — all while honoring the legacies of ancestors by preserving their techniques.

U.Va. is the home of the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, which is the only museum outside of Australia purely dedicated to art from Aboriginal Australians, thanks to the donated collections of John Kluge and Edward Ruhe.

Because of the presence of Aboriginal art in Charlottesville, Yolngu leader W. Wanambi wanted to strengthen the rich relationship between these two vastly different geographical regions. He played an integral role in the creation and curation of “Madayin,” but passed away three months before the exhibition opened in 2022 at the first venue of its tour, the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth. In his lifetime, Wanambi took many long journeys from Australia to Charlottesville where he masterfully developed the exhibit.

“[The exhibit] is an incredible testament to his courage and willingness to cross boundaries, and work with institutions to change the ways in which museums operate,” said Henry Skerritt, assistant professor and Kluge-Ruhe curator of Indigenous Arts of Australia.

A part of the innovation and change that Skerritt is referencing is the structure of the exhibit. Both unique and extremely intentional, the physical space is meant to represent vital Yolngu systems of belief.

“Madayin” is based on a key Yolngu concept known as Dhuwa and Yirritja. This concept splits everything in the world into either Dhuwa or Yirritja, similar to Yin and Yang. To demonstrate this quintessential duality, “Madayin” is split in two. As one enters the actual gallery space, you choose which way to go — either left for the Yirritja side or right for the Dhuwa side. The art displayed on each side is symbolic of your choice, and at the center of the gallery Dhuwa and Yirritja meet as one, representative of the Yolngu belief in the interconnectedness of the world, known as “Country.” To try and put a very complex and significant term into just one sentence, “Country” describes how everything living and in nature and spiritually is connected.

Artist Gunybi Ganambarr explained that this total, all-encompassing idea of reality and connectedness is the reason why the flowing water visual is displayed at the entryway. As Ganambarr describes, water connects us all, and we all interact with it.

“We cross the river and we bring water from that end to this end to meet other people and other nations … sharing the knowledge and carrying the knowledge,” Ganambarr said.

Mayatili Marika, a deeply influential Yolngu leader for education and advocacy, further articulated this idea of connection.

“We are not just related to each other as humans, but we are related to everything else within the cosmos as well,” Marika said.

Many of the pieces in “Madayin” are themselves concerned with human connection — specifically connections across cultures. One piece — “Journey to America” by co-curator Djambawa Marawili — serves as an example of the contemporary nature and bridging of culture in Yolngu bark painting.

In Marawili’s piece, there is a depiction of the Statue of Liberty at the very top, while the Australian coat of arms is emblematically placed in the lower left. The combination of imagery from the United States and Australia highlights the ever-growing connection between the two nations, and the history of bark painting shows the connection of past to present.

Symbolic of this international connection is Dhukumul Wanambi, daughter of W. Wanambi. She traveled to the United States for the opening of “Madayin” at the Fralin in honor of her father and his love for sharing his community’s art and deeply-rooted traditions.

Marika discussed the importance of this long-lasting familial legacy for Yolngu artists working as a part of “Madayin.”

“[The elders] paved the way for us to be able to come here to places like Charlottesville and other places in America through mediums like the “Madayin” exhibition … it is a great honor to be able to keep showing our art and culture to audiences throughout the world,” Marika said.

The curators of “Madayin” — Marawili, Wanambi, Skerritt, Yinimala Gumana, Wäka Mununggurr and Kade McDonald — alongside the Yolngu artists and innovators who have contributed to the exhibit, have effectively elevated the voices of Aboriginal artists on an international scale in the art world.

The “Madayin” exhibit is a part of Charlottesville’s Indigenous Art Takeover — a program that includes five different Charlottesville-area exhibits, all of which center Indigenous art in Oceania and Australia. Each exhibit in the Indigenous Art Takeover will be open at different times, with the final one closing on July 14 — giving audiences ample opportunities to experience internationally famous and profound pieces.