Hood Museum of Art Quarterly, Fall 2022

Make sure to pickup or download a copy of the Fall 2022 edition of the Hood Museum of Art Quarterly. It features a fantastic interview between Jami Powell and Henry Skerritt on the curatorial process behind Maḏayin.

The following interview was conducted in June 2022 between Jami Powell, curator of Indigenous Art, Hood Museum of Art, and Henry Skerritt, assistant professor in the Department of Art at the University of Virginia and Curator at the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia. It has been edited for clarity and length.

Jami Powell (JP): Where did the idea for the Maḏayin exhibition come from?

Henry Skerritt (HS): The idea was devised in September 2015 by Djambawa Marawili, and I can pinpoint the time and date very precisely because he, Kade McDonald, and I were at the Three Notch’d Brewery in Charlottesville. Djambawa had been in Charlottesville for two or three days, and he’d had a chance to look over the Kluge-Ruhe collection. I think he was quite moved to see so many Yolŋu bark paintings there, and also to see all the photographic documentation of the 1996 John Kluge Yirrkala commission.

At Kluge-Ruhe, there are beautiful photos from 1996 of Djambawa and his father, Wakuthi Marawili, as Djambawa worked on his painting Maḏarrpa Miny’tji | Maḏarrpa Clan Designs (1996), which won the Bark Painting Award at the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards that year. That was a big win for Djambawa, but more importantly, it occurred at a pivotal moment in his life. Wakuthi was getting quite old, and Djambawa was rising to become the leader of the Maḏarrpa clan. Djambawa was impressed, moved, and very surprised to see so many Yolŋu paintings in Charlottesville. He said to us,

“Oh, that’s good, but what we need is an exhibition that tells the whole story.” For him, it was very clear that that whole story began when Woŋgu Munuŋgurr painted the first bark for the anthropologist Donald Thomson in July of 1935, and that the story extended to the present.

But it was just as important to him that the exhibition include young, up-and-coming artists like Yinimala Gumana and Gunybi Ganambarr. What’s important to understand is that for Djambawa, the “whole story” wasn’t just looking backward at this history, but also looking forward and thinking about the future. In his essay in the exhibition catalogue, he writes a powerful message to the young generation of artists: “To the Yolŋu rising today, do not stop at the surface: you must make your identity a priority for all our elders. And that is why we Yolŋu must work together, because this is an opportunity to learn to curate and show our culture to the world.”

JP: Djambawa proposed a big project. How did you go about developing the project and begin working collaboratively?

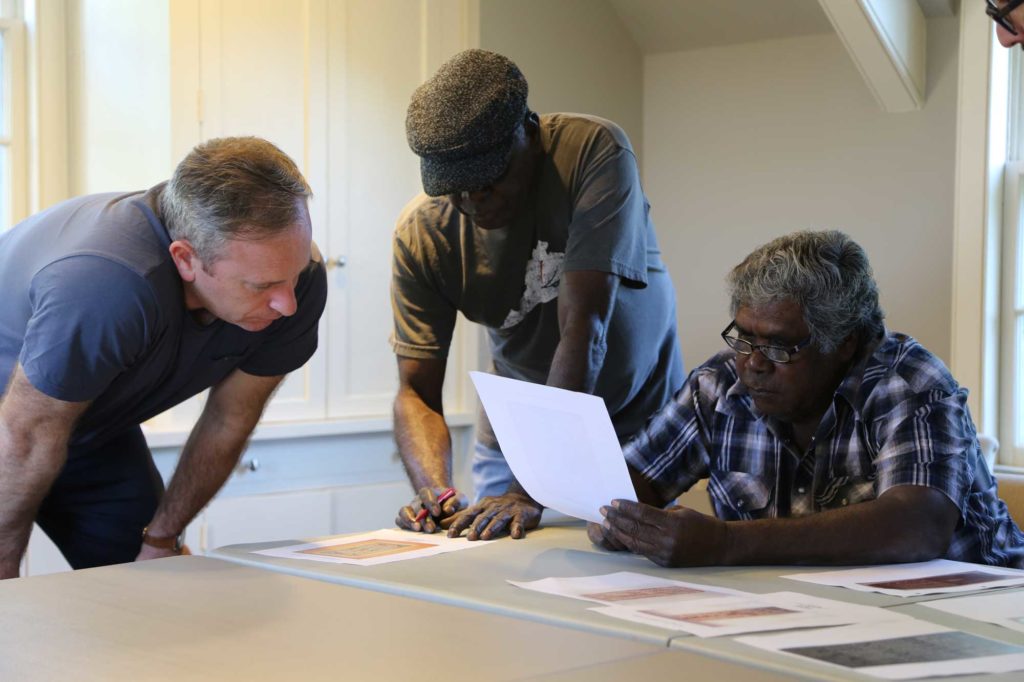

HS: From the beginning, we knew that, if we were going to do this, it had to be led by Djambawa. So, we put it to him that he needed to be the lead curator, and it had to be a Yolŋu driven project. He thought about this and then deputized Wukuṉ Waṉambi and Yinimala Gumana to come to the United States to begin that process.

JP: Speaking of beginnings, you mentioned the emergence of bark painting as an artistic practice and how that was entangled with the work of anthropologist Donald Thomson. Can you talk about that history?

HS: That’s a slightly controversial question. In general, it’s clear that Yolŋu people and other Indigenous people across Australia have used bark in many different ways over time. It is a very versatile medium; you can make it into a bag, or a shelter, or a canoe. But I am not sure how common it would have been to paint sacred designs on bark—like you see in this exhibition— in the precolonial times. This, however, is a topic of debate, and I’ve heard Yolŋu make different arguments about this. More often, these designs would have been painted on the bodies of young men when they were being initiated. In the 1930s, these same designs began appearing on bark. The work Mundukuḻ ga Yirwarra Dhäwu | Ancestral Snake and Fish Trap Story (1942) by Mundukuḻ Marawaili is a good example of this. It is a literal transcription of body painting, to the extent that the artist has included bars at the top and bottom, which would be painted on the shoulders and thighs of initiates. So, it is clear that in the 1930s and 1940s, artists were taking body painting designs and transferring them to bark. But very quickly, things started to change as artists began to fill up the whole surface of the bark and bring in different figurative motifs.

JP: We’re fortunate enough to have one of the earliest barks in this show, right?

HS: Yes. In fact, we have the very first painting that Woŋgu Munuŋgurr did in 1935. That’s a special thing to have coming to the United States, leaving Australia for the first time.

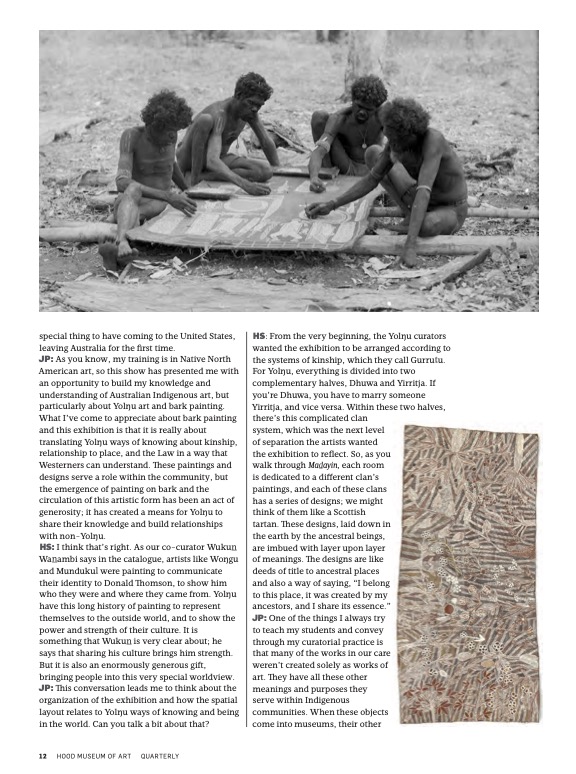

JP: As you know, my training is in Native North American art, so this show has presented me with an opportunity to build my knowledge and understanding of Australian Indigenous art, but particularly about Yolŋu art and bark painting. What I’ve come to appreciate about bark painting and this exhibition is that it is really about translating Yolŋu ways of knowing about kinship, relationship to place, and the Law in a way that Westerners can understand. These paintings and designs serve a role within the community, but the emergence of painting on bark and the circulation of this artistic form has been an act of generosity; it has created a means for Yolŋu to share their knowledge and build relationships with non-Yolŋu.

HS: I think that’s right. As our co-curator Wukuṉ Waṉambi says in the catalogue, artists like Woŋgu and Mundukuḻ were painting to communicate their identity to Donald Thomson, to show him who they were and where they came from. Yolŋu have this long history of painting to represent themselves to the outside world, and to show the power and strength of their culture. It is something that Wuku is very clear about; he says that sharing his culture brings him strength. But it is also an enormously generous gift, bringing people into this very special worldview.

JP: This conversation leads me to think about the organization of the exhibition and how the spatial layout relates to Yolŋu ways of knowing and being in the world. Can you talk a bit about that?

HS: From the very beginning, the Yolŋu curators wanted the exhibition to be arranged according to the systems of kinship, which they call Gurruṯu. For Yolŋu, everything is divided into two complementary halves, Dhuwa and Yirritja. If you’re Dhuwa, you have to marry someone Yirritja, and vice versa. Within these two halves, there’s this complicated clan system, which was the next level of separation the artists wanted the exhibition to reflect. So, as you walk through Maḏayin, each room is dedicated to a different clan’s paintings, and each of these clans has a series of designs; we might think of them like a Scottish tartan. These designs, laid down in the earth by the ancestral beings, are imbued with layer upon layer of meanings. The designs are like deeds of title to ancestral places and also a way of saying, “I belong to this place, it was created by my ancestors, and I share its essence.”

JP: One of the things I always try to teach my students and convey through my curatorial practice is that many of the works in our care weren’t created solely as works of art. They have all these other meanings and purposes they serve within Indigenous communities. When these objects come into museums, their other meanings can fall away. The approach to this exhibition and its organization rejects that decontextualization.

One of my favorite works in the show is the diptych by Mulkuṉ Wirrpanda, Retja (Rainforest) I & II (2017), because it is such a great example of the kind of work that was created for the market but also serves these other purposes. In the painting, Mulkuṉ has painted all these medicinal and edible plants. It is a stunning work of art, but Mulkuṉ also maps out the plant species and lists their names and uses. Therefore, this work becomes an important means for transmitting cultural knowledge and understandings, both within the community and beyond it. It also enables a deeper understanding about our relationships, as humans, to nonhuman beings and the reciprocity embedded in those relations, and the diptych does so in a beautiful and meaningful way.

HS: In addition to showing the artists’ identity and connection to place, it was important for the Yolŋu curators to enable audiences to recognize different ways of being in the world.

JP: Is that what you hope audiences, and US audiences in particular, will get from this exhibition?

HS: Definitely. But as an art historian, I would also like visitors to recognize this as an extraordinary artistic tradition—one that has not been still over the last 80 years, but has reacted to its times while also staying true to its traditions and meanings. There’s something amazing about an art movement that can be 50,000 years old and still finding exciting and dynamic ways to repeat the same combinations of diamonds and grids and crosshatching.

I also think that when US audiences approach Indigenous Australian art, they often come to it asking “How can we help these poor, underprivileged people?” Many people do not realize, for example, that the Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Center, where many of the works in Maḏayin originate, is not a tin shed; it is a multimillion-dollar company owned and directed by Aboriginal people. Djambawa and the Yolŋu curators see this exhibition as an opportunity for the world to learn from them and the gift of their knowledge. I think the exhibition also presents an opportunity to open up dialogues between Yolŋu and Indigenous nations in the United States and around the world, as well as for other Indigenous peoples to take inspiration from this project and to collaborate with Yolŋu. Maḏayin is their gift to the world, and it is powerful.