Originally published in The Daily Progress February 3, 2024.

A new exhibit opening this weekend begins by sweeping viewers back in time.

“Madayin: Eight Decades of Aboriginal Australian Bark Painting from Yirrkala,” which opens Saturday at the Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, premiered at the Hood Museum of Art in Dartmouth in September 2022 before heading out on a national tour that led it back to its Charlottesville connections.

The idea for bringing the paintings together and sharing them with the world came to Yolŋu artist and leader Djambara Marawili in 2015 during his residency at Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection at UVa. But the origins of the artworks, and the generations of creation stories and family bonds that give them life, go back far deeper into history.

When asked Thursday how long it takes to complete one of the intricate paintings on painstakingly prepared and cured eucalyptus bark, Henry Skerritt, Kluge-Ruhe curator and assistant professor of art history at UVa, responded, “About 65,000 years.”

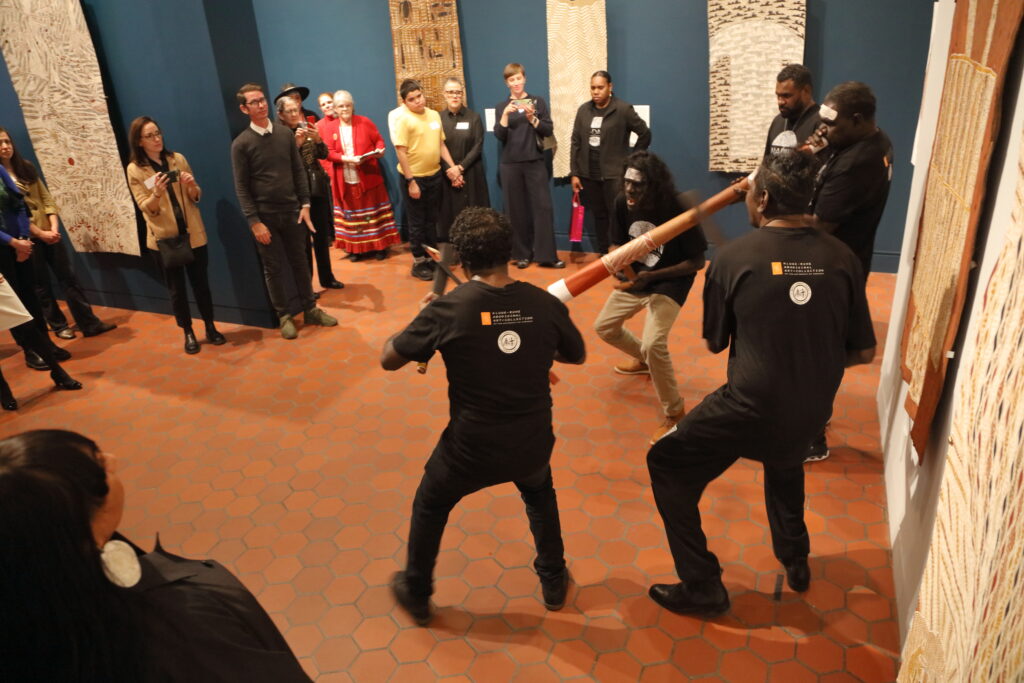

A six-member delegation of Yolŋu artists and curators who attended a media preview Thursday at the Fralin explained how the paintings on display reflect not merely aesthetic principles, but also a rich oral history handed down from parent to child and grandparent to grandchild.

“It’s art to an outside eye, but to us, it is text,” said Mayatili Marika, who will present the W. Wanambi Distinguished Lecture at 4 p.m. Saturday in the Dome Room of the Rotunda. “It’s multifaceted and multidimensional.”

Even her talk will make connections, tying in “Madayin” with another exhibit, “Waŋupini: Clouds of Remembrance and Return,” which will remain in the Upper West Oval Room at the Rotunda through July 8.

In the Yolŋu culture, storytelling is an important way to convey intricacies of family history and the behavior of natural world. What can sound like a tangent to someone outside the culture can offer vital information about connections among family and community members to someone who cherishes the stories.

“We talk in spirals. To get from Point A to Point B is not linear,” Marika said. “Each and every thing that exists — everything on the seas, the land — fits into a finite space in the cosmos. Just as the tides go in and out, so do guests, and knowledge.”

A video of crashing ocean waves, accompanied by traditional singing paired with didgeridoo and percussion, spans a wall to greet visitors climbing the stairs to see “Madayin” at the Fralin. It extends a welcome to visitors as they enter the realm of the paintings and their stories of connection.

Dhukumul Wanambi, 20, took time to explain the background of “Destiny,” a bark painting by her father, Wukun Wanambi. A small mullet-like fish swims through rivers, creeks and oceans in search of his destiny, which he discovers while he is surrounded by his family.

Other paintings document the traditional motifs that would have been painted on a human body during ceremonies. “The shimmering power of it is the ancestors still occupy your mind,” Skerritt said. “You’re only seeing the surface.”

Attention shown to the artworks serves different purposes in different cultural environments. Westerners often are far more impressed by prestigious international accolades the artists have won for their paintings, while the artists themselves are more gratified to see how modern technology and wider exposure can bring the stories they treasure to wider audiences and new generations, Skerritt said.

Marika’s lecture is one of a dozen events connected to the exhibition. The artists led a tour of “Madayin” on Friday afternoon, followed by a First Fridays reception.

Other local galleries have opened complementary exhibitions, including Second Street Gallery’s “First Nation Australia: Contemporary Artists from the Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala,” which can be seen through March 22, and “Ukapalamin: Eti Ko Eti: Resilience: Stories from the Torres Strait,” on view through April 22.

Already on view at the Fralin is “Voices of Connection: Garamut Slit Drums of New Guinea,” which features handmade drums capable of communicating over long distances to connect people in remote areas who otherwise could be hard to reach.

“Madayin” is organized by Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection at UVa in partnership with the Buku-Larrngay Mulka Center in Australia and curated by Djambara Marawili, W. Wanambi, Yinimala Gumana, Waka Munungurr, Henry Skerritt and Kate McDonald.

“Madayin” can be seen at the Fralin through July 14 before moving to the Asia Society in New York, where it will open in September.