Yiŋapuŋapu

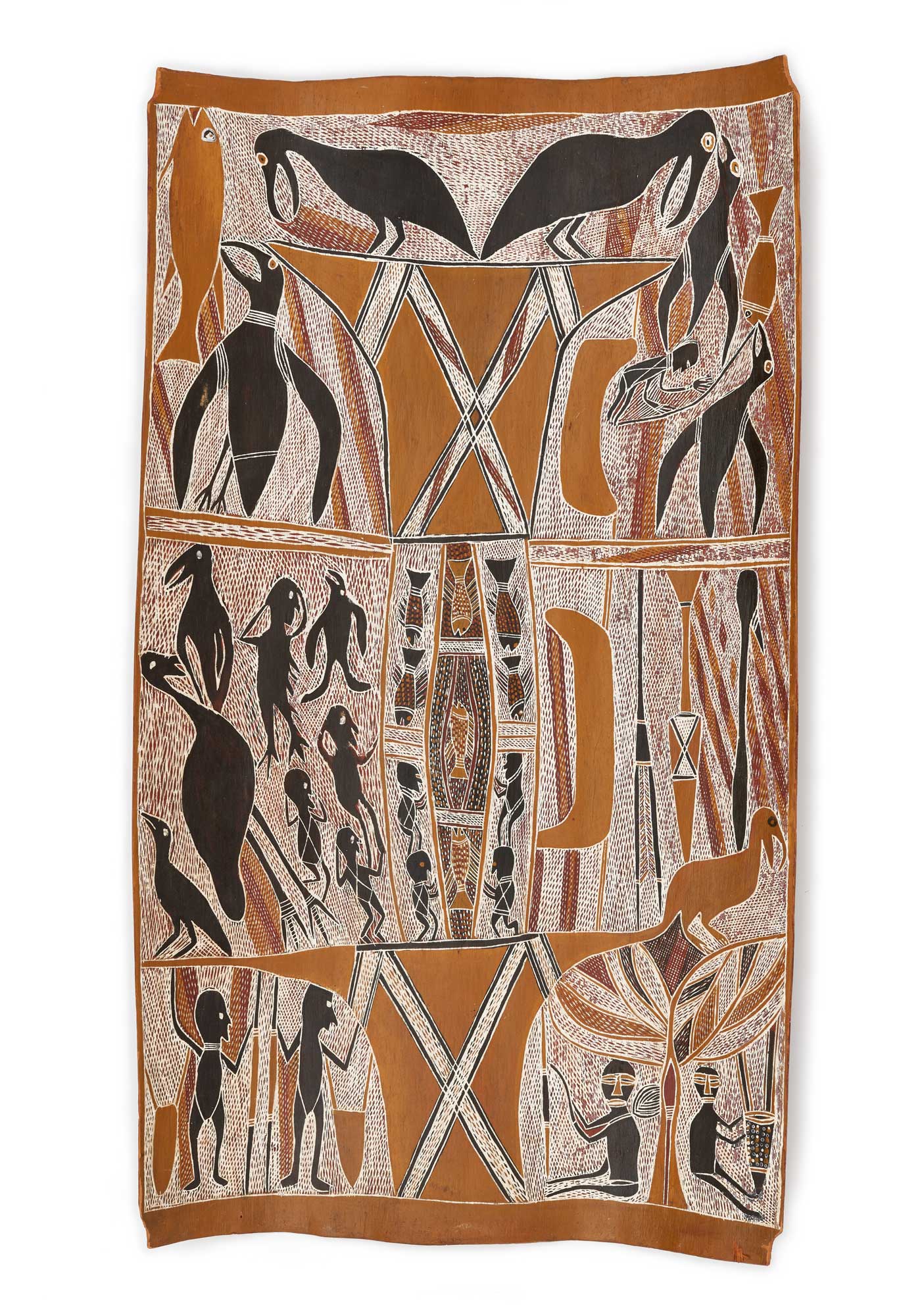

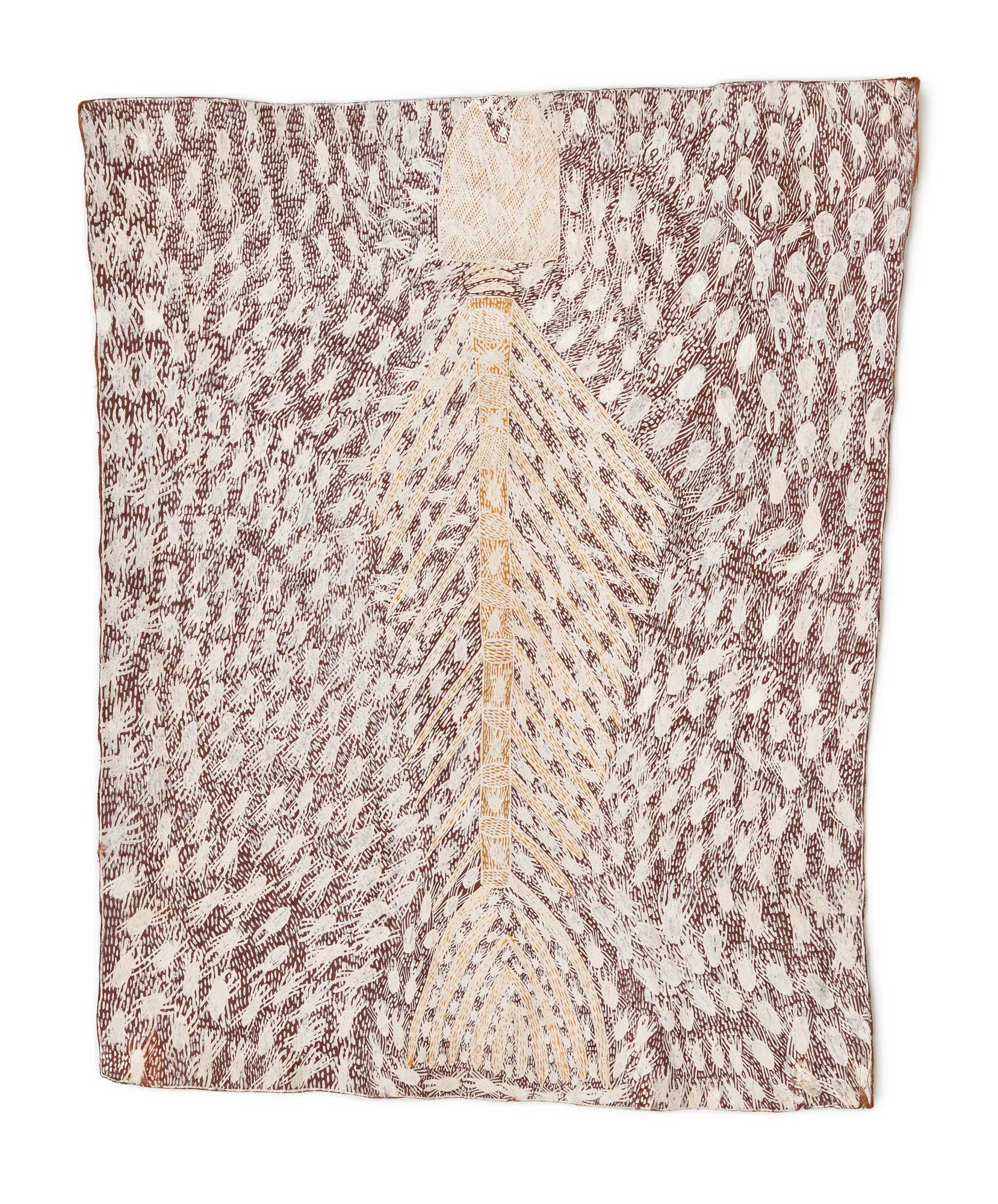

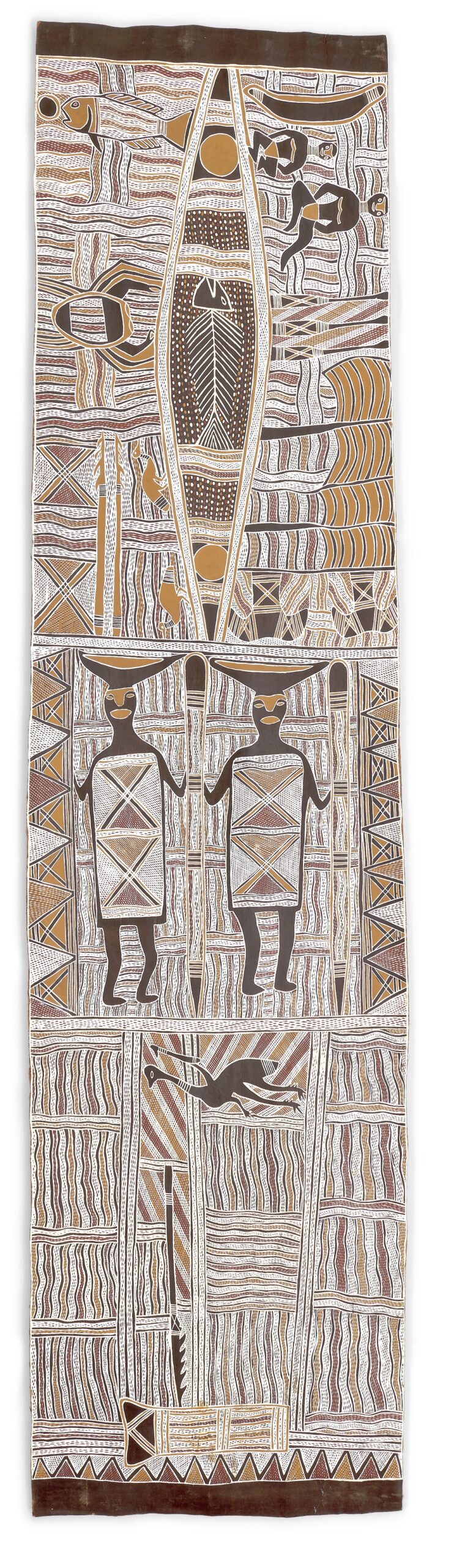

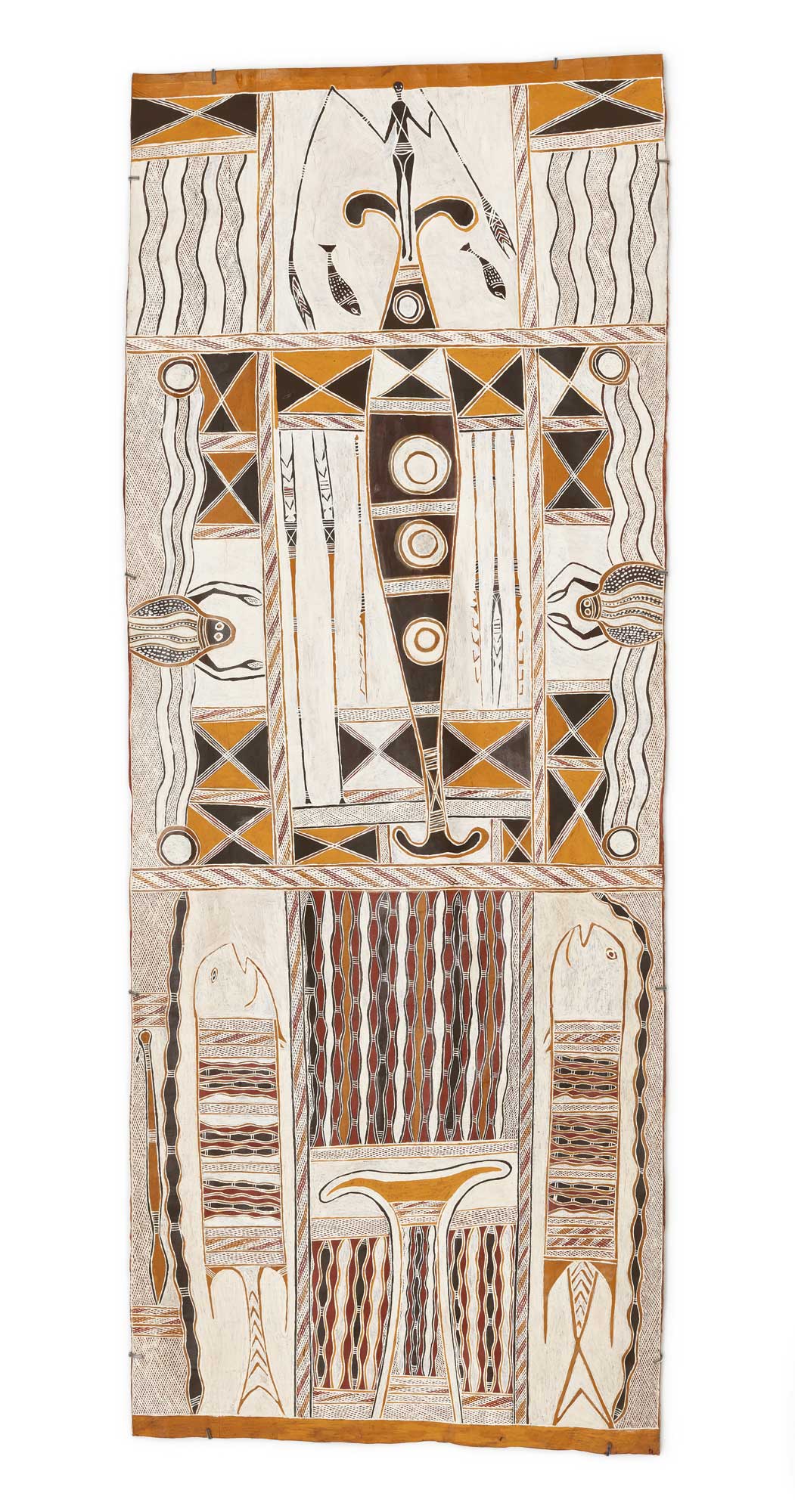

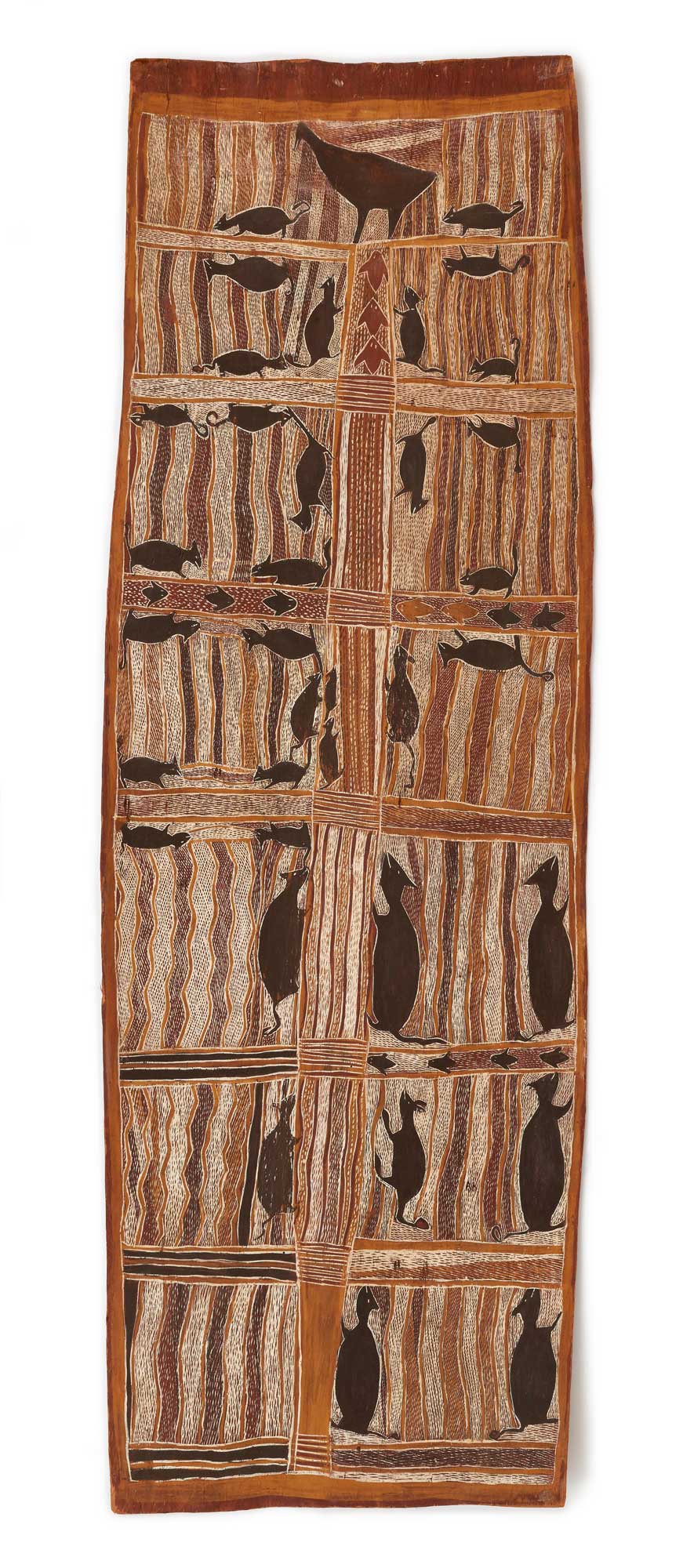

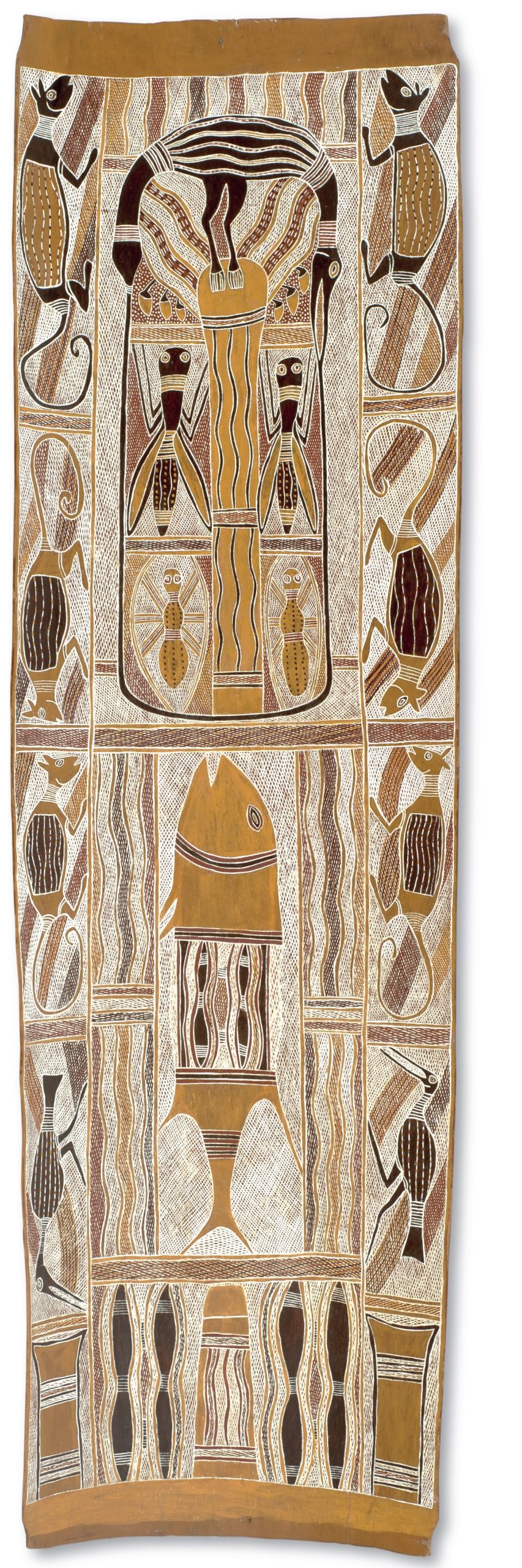

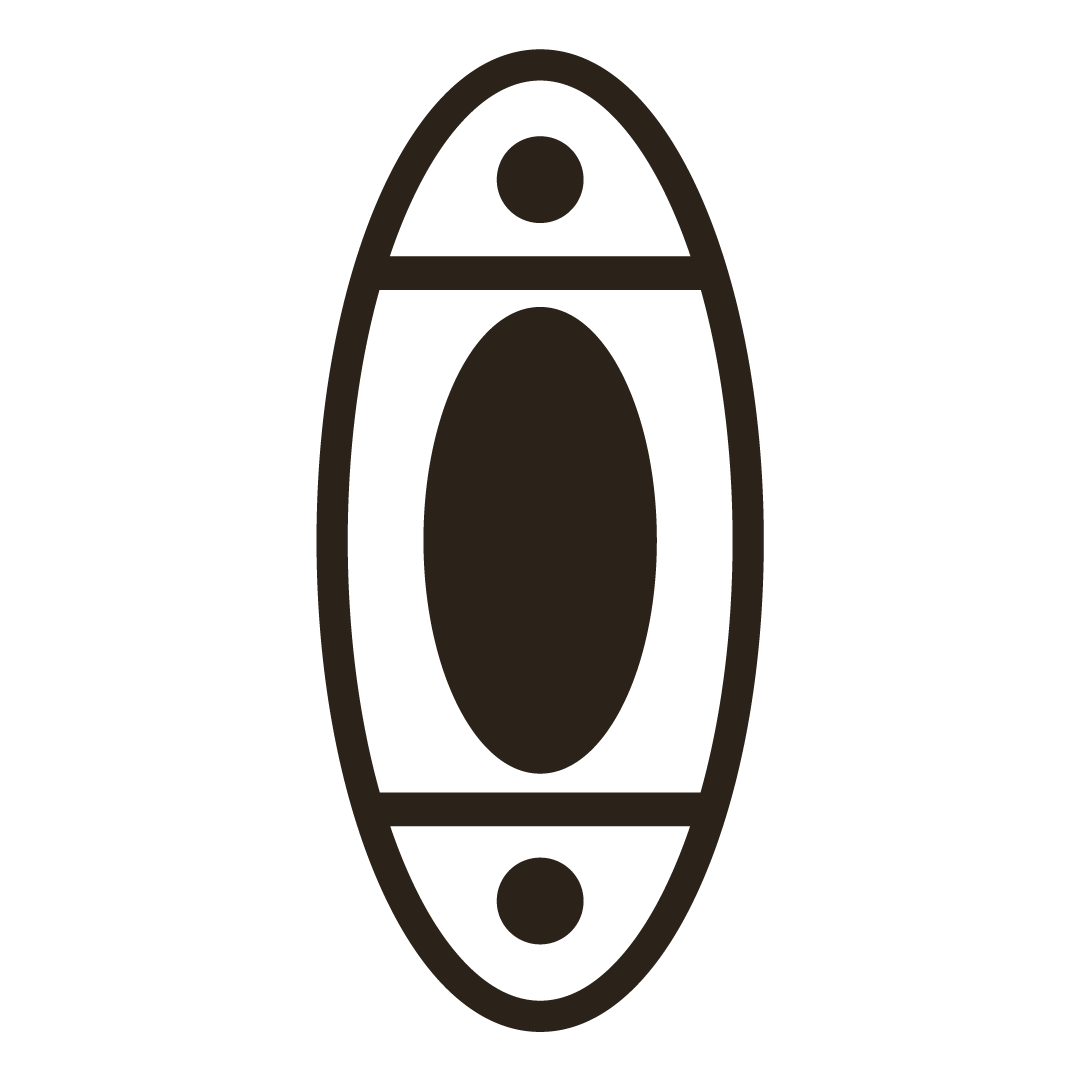

The yiŋapuŋapu is a low relief sand sculpture, elliptical in shape, that is used in the mortuary rites of the Yirritja clans of Maŋgalili, Madarrpa and Dhalwaŋu. Its primary traditional function is to keep the contamination of death within the confines of the sculpture. Traditionally the body of the deceased was placed within it for initial mortuary rites, to cleanse the bones of dangerous spirits held within the body tissue. In days before European contact, placement of the deceased within the yiŋapuŋapu on the associated clan land had been reserved originally for the Creator Ancestors. A metaphor for this action of cleansing is utilized by the Maŋgalili clan in their sacred paintings depicting Mirriya or Gunyan, the sand or ghost crab picking the bones of a fish carcass on the beach. In traditional mortuary ceremonies for these clans, the last act is to catch and eat yambirrku’ (the blue tusk fish, Choerodon cyanodus) and dispose of the bones in the ceremonial sand sculpture for the crabs to pick clean overnight. On the beaches of Djarrakpi contemporary Maŋgalili put their food scraps in one place when at camp – the secular yiŋupuŋapu. Today, there are permanent yiŋupuŋapu located at Ḻuŋgutja, Djarrakpi, Bäniyala and Garrapara.

I’ll just tell you about yiŋapuŋapu (burial ground). That is more in the open and appropriate to talk about. I won’t talk about Ŋärra’ (senior men’s Law). That maḏayin is sacred Law. That is the Law for those places where sacred closed ceremonies and men’s business take place; that is where the sacred Law stands. In those places, a person’s actions must be sanctified, so no children, or women, or Yolŋu who are not connected to that Law are allowed to enter. Authority resides in the djuŋgayi (ceremonial manager). Yes, only the djuŋgayi is to speak. And only those certain people who have been chosen must take care of that sacred business. We must ensure that this authority is respected here at Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre.

Yiŋapuŋapu means burial ground. And it also means a place where we throw bones or flesh. We bury it in that particular ground and it becomes rotten. It becomes rotten, it’s true. We collect all the eggshells and the bones and flesh of the fish, and they are thrown into that burial ground. There are three yiŋapuŋapu where scraps are thrown. Yes, there are three clan groups that hold this ritual: my clan group, Maŋgalili, is the third, but my grand- mother’s clan group, Dhaḻwaŋu, has the first yiŋapuŋapu. This ritual is practiced in Bäniyala [by the Maḏarrpa clan], in Garrapara [by the Dhaḻwaŋu clan] and in Ḻuŋgutja. So, there are actually four yiŋapuŋapu, if you include mine: Ḻuŋgutja, Djarrakpi, Yilpara/Bäniyala and also Garrapara. And these three groups—Maŋgalili, Maḏarrpa and Dhaḻwaŋu—all sing of the same saltwater.

– BALUKA MAYMURU

My father did not want to go and stay in that particular area; he wanted us to stay right here, where the yiŋapuŋapu (ceremonial sand sculpture, or sacred burial ground) is. Some other families did stay near that sacred area. And that was fine, as long as they stayed away from the particular area where ceremonies were performed. They could stay there, provided they were not too close to where that sacred area is, for it holds sacred paintings and stories. The moral of this story is that the paintings, the songlines and the ancestral stories tell us where it is appropriate to go and where there are sacred areas that we are forbidden to go to. And so, we had this land Bäniyala where the yiŋapuŋapu is located.

Yiŋapuŋapu is a place where you can sit to build a home so that the tribe can expand and make their clan nation big. There is also a place called Gäṉgaṉ that has the same significant Law, and it is now also a homeland. But we stayed there at Bäniyala at the yiŋapuŋapu. When we die, our bodies will return to this place to be buried in that particular ground called yiŋapuŋapu. I used to hear my father say, “Do not go to that sacred area, because it is forbidden to go there.” He called that place Marthaŋa, which confused me, because it is the word for “ship.” I thought he was referring to a boat, but what he meant was an open area where they have sacred ceremonies. And so, this place, which is also called Rirrwalwuy, is a place where our bones and our flesh and blood return back to that soil. Rirrwalwuy is another name for this place, Bäniyala; our spirit will return to that place of the yiŋapuŋapu. The sacred place that my father would talk about was the other side, a place called Yathikpa: this is the name that the old people gave for everyone to use.

– DJAMBAWA MARAWILI

Filter By

- Select a Filter

- Clans

- Songlines

Selection